Ishmael Reed managed to escape my attention until someone mentioned his play The Haunting of Lin-Manuel Miranda in a podcast I was listening to. In lieu of being able to see it staged (I guess I could still read it…), I added his novel Mumbo Jumbo to my TBR. However many years later, I found a copy of it at a bookstore in Chicago. (Not the same one where I found Refuse to Be Done, for anyone keeping track at home.)

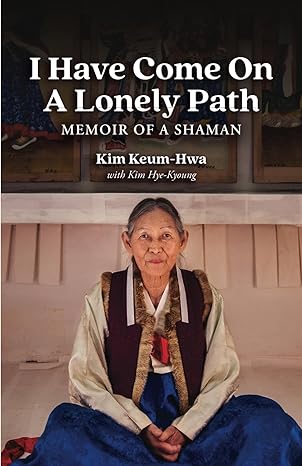

The Knights Templar, along with the fictional Wallflower Order, are at work during the 1920s to stop a virus called “Jes Grew,” originating in Black culture and music, that leads to a sense of euphoria uncontrollable dancing. Working against them is PaPa LaBas, a Vodou priest on the trail of a MacGuffin that, united with the virus, will bring an unprecedented new age of freedom and human expression. The Knights, of course, want this MacGuffin destroyed. In the end LaBas is unsuccessful, but fifty years later LaBas is confident that a new opportunity to bring Jes Grew and another iteration of the MacGuffin together is waiting just around the corner, noting that several cultural trends of the 70s are identical or similar to the ones that gave rise to the virus in the 20s.

That summary does a huge disservice to the book, though, since all of that plot is really there as a vehicle for satire and social commentary. It reads a lot like the Illuminatus! trilogy, or what I remember of it anyway, except I never felt like Illuminatus! should have been part of my literary education. In that sense, Mumbo Jumbo has more meat on its bones. It’s another title for my list of “books that I am surprised (not really) were never assigned reading,” which started with No-No Boy in 2017.