Hands up who read “The Lottery” for English class at one point.

Yeah, me too.

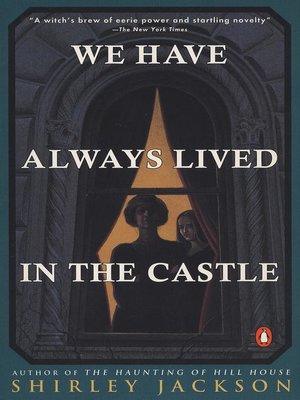

And that’s about where all of my Shirley Jackson reading stopped off. The Sundial was a selection for the Austin Feminist Sci-Fi Book Club a while back and I didn’t really care for it. Even now I barely remember it (which is why I like to keep this little book blog going). But We Have Always Lived in the Castle is a title people mention all the time; moreover, it was esteemed enough a book to remain in one half of my Austin hosting couple’s library after several years of purging and downsizing. Based on that, I figured the odds (please insert your own joke about odds and lotteries here) were pretty good that I’d enjoy the book. If nothing else, reading it would allow me to partake of a very particular moment of a friend’s life and a specific facet of their personality, and that alone is worth it.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle did not fail to deliver!

Following the death of their family from an unsolved case of arsenic poisoning, Mary Katherine (Merricat) and Constance Blackwood, sisters, have secluded themselves in the ancestral home together with their Uncle Julian. Constance no longer leaves the property beyond her garden, leaving Merricat in charge of going into the village—whose residents have long been hostile to the Blackwood family and who are all convinced of Constance’s guilt in the arsenic case—to fetch groceries and items as necessary. This comfortable norm is interrupted by the arrival of cousin Charles, who has decided to reach out to this estranged branch of the family after the death of his father (brother to Uncle Julian and to the late patriarch of the Blackwood family). Charles and Constance strike up a relationship while Merricat immediately dislikes this interloper and does everything she can to drive him away.

Now that I’ve finally read the book once, I’d love to read it again and chart exactly how Jackson manages to ratchet up the spooky and the tension. (How appropriate that this review is going up as we gear up to enter Spooky Season!) I think the two hardest things to write are comedy and horror, because what people find funny and what people find terrifying are pretty personal at the end of the day. When a book succeeds in one of those genres, I think it’s worth paying extra close attention to figuring out why.