Unless you went to high school with me, you probably don’t know that I played the violin in orchestra.

Well, now you do, I guess?

I was never particularly good, let me be clear. It would be fair to say I was a perfectly mediocre violinist. Nonetheless I enjoyed orchestra and continued throughout my entire high school career, concert orchestra as well as pit orchestra. I don’t really think about the violin very often—usually only when I listen to a particular symphonic piece we performed, where my memory of it is more deeply embodied than with other music. Who knows, maybe my brain is still sending phantom signals to my lefthand fingers and bow arm.

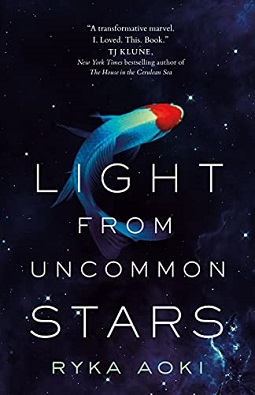

Light From Uncommon Stars, on the other hand, made me think about the violin a lot.

Our heroine is Katrina Nguyen, a trans teenager and gifted violinist. Legendary violin instructor Shizuka Satomi hears Katrina playing in a park and decides to take her on as a student so she can complete her Faustian bargain with the demon Tremon Philippe and deliver Katrina’s soul to Hell. Alien refugee and spaceship captain Lan Tran has fled to Earth with her family and fallen in love with Shizuka after she visits the donut shop Tran runs as a cover operation for constructing a stargate.

Catch all that?

There is a lot going on in Light From Uncommon Stars, and while it’s at times a fun and dizzying combination of science fiction and demons from Hell and classical music, sometimes it’s a bit too much. Memories and flashbacks appear out of nowhere without adding anything to the story or its characters. Shizuka’s grand declamations and philosophical reflections about the power of musical performance are at once too long and too shallow to really ring true for me. All of this crowds out more interesting material for me, like Katrina’s genuinely insightful and touching reflection on gender identity through the metaphor of Bartok’s Sonata for Solo Violin.

Nor does Aoki flinch from at least gesturing at the more traumatic events of Katrina’s previous life, which don’t always blend well with the wacky feel-good sci-fi hijinks. There were moments where it hit something like anti-lagom (mogal?), exactly wrong instead of exactly right: what should be goofy space shit feels a bit out of place compared to what just happened in the last chapter; betrayal that would take a lot of time and therapy to work through in the real world is brushed aside almost immediately to get our wacky plot on the road.

But there are violins.

According to her author bio, Aoki is also a composer. This is hardly surprising given the countless musical references, including several to—of course—Paganini. (And yet, apparently Tartini’s “Devil’s Trill Sonata” was too on the nose for Aoki to use here? Missed opportunity, if you ask me.) I don’t know if Aoki is also a violinist, but whether it was lived experience or impeccable research, many of the violin-specific asides landed for me in an almost visceral way; the same embodied memory as when I hear a piece I performed in orchestra. “Does she need some tape on her fingerboard?” is one withering remark from the antagonist about Katrina’s inexpertise that made me cringe in shame: that controversial, or at least pedestrian, method was how I had been taught. Crappy rosin in plastic cases. Tuning forks. The way it feels to slide a wire mute over the bridge. Viola jokes. (Or, well, one viola joke. Which was mostly implied.) All of that was an absolute delight, to the point where I began to get a bit irritated when the book wasn’t talking about music. (Or food. Lots of food in this book. Her bio doesn’t mention it but I bet Aoki would call herself a foodie.)

Violins, however, are not enough. To put it bluntly, there was a lot in Light From Uncommon Stars that was simply not written for me. I don’t mean that because of the subject matter beyond my own lived experience (I’m not Asian, I’m not trans), but rather on a more “philosophy of reading” level.

Any conflict not immediately related to the relationships between Shizuka, Katrina, and Tran inevitably comes to a pat conclusion within a page or two. Minor villains are either destroyed immediately after their appearance (a racist storeowner drops dead of a heart attack half an hour after he disses Katrina’s violin; the emcee of a talent showcase who makes transphobic jokes at Katrina’s expense suffers a housefire), disappear entirely from the narrative (Katrina’s awful roommates), or are declared irredeemably toxic by Implied Word of God and summarily consigned by Katrina to the memory hole with no mourning or regret (Katrina’s parents). All of these had the potential to be the site of really thoughtful consideration and nuanced storytelling, but Aoki just sidesteps them, which then inspires the question of why include those conflicts or characters in the first place.

Everything neat and tidy, warm fuzzies and bear hugs for everybody.

I get why people want that in a book. I get in that mood sometimes, too. But I wasn’t in that mood when I picked up Light From Uncommon Stars so I had a hard time enjoying the book on those terms. Settling back into my violinist body, though? Even for just a couple of hours? That’s what I’m here for.