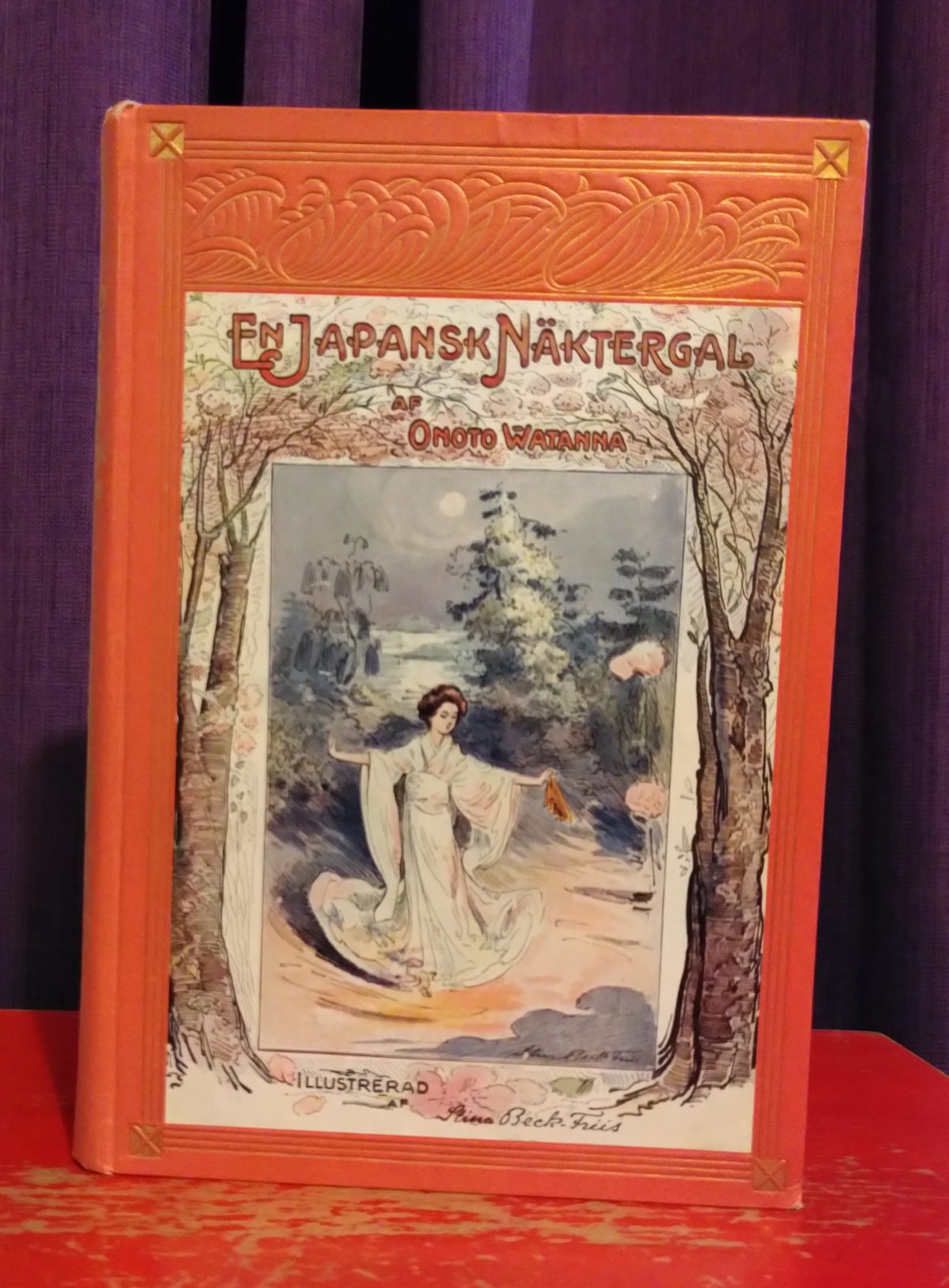

My sambo has tremendous thrift shop karma, which is how I came to be in possession of this lovely hardback book, a Swedish translation of an English melodrama/romance by Winnifred Eaton writing under the pen name Onoto Watanna*: A Japanese Nightingale.

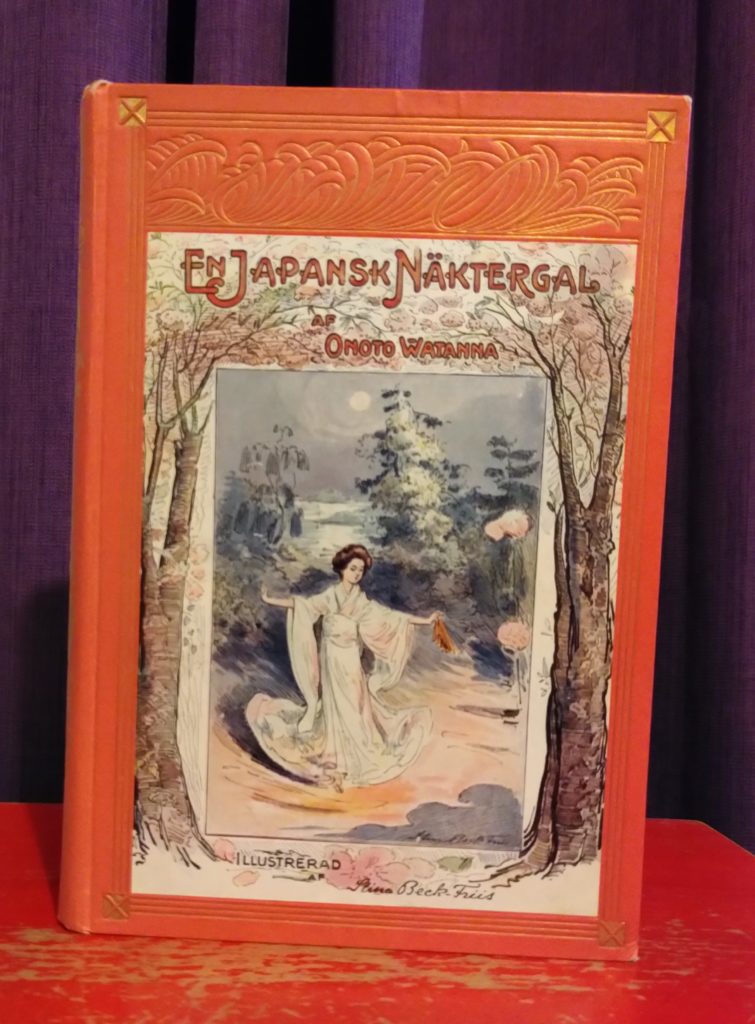

As a hardback book from 1907 with several full color illustrations, it seems like it should be kind of rare and expensive, yet the going price for this book on Bokbursen wasn’t anything more expensive than your standard new paperback release and there were several listings for it. I guess it just goes to show how much I don’t know about actual book collecting.

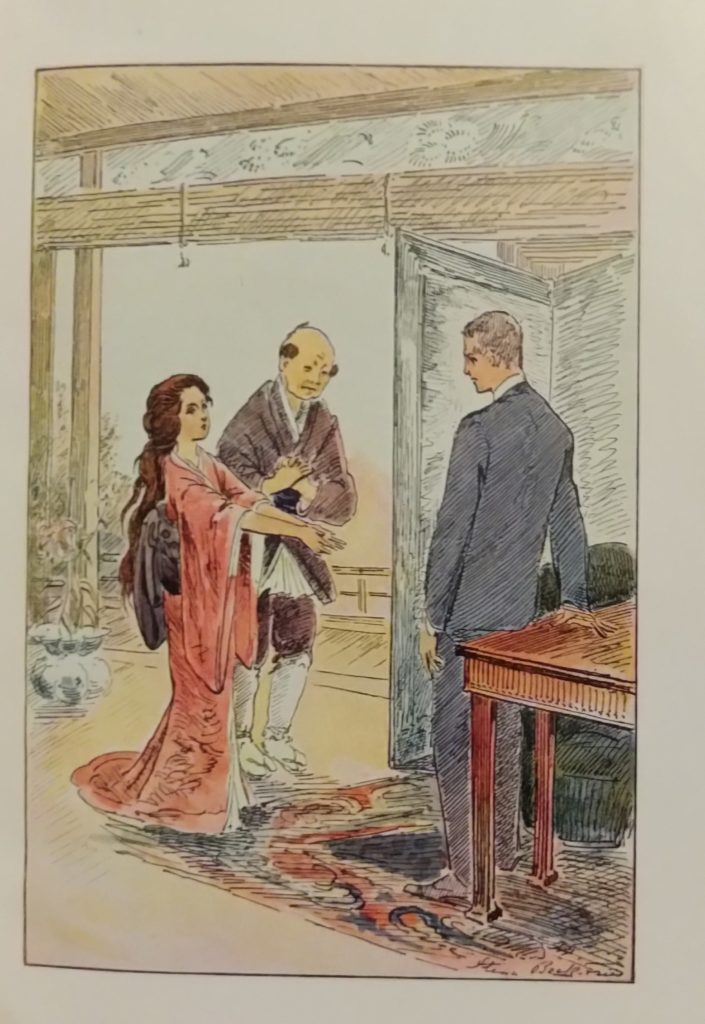

All-American wealthy playboy Jack Bigelow is in Japan for unclear reasons. While he is waiting for his mixed-race friend Taro to come join him, Bigelow marries Yuki, a charming and mysterious mixed-race geisha. Even as Bigelow reflects on Taro’s contempt for foreigners who take temporary Japanese wives, he lets himself be talked into just such a marriage. Still, their relationship is a happy one, except Yuki’s mood swings and constant requests for money. Bigelow acquiesces, though not without misgivings and suspicions.

Taro finally arrives and—here’s a shocker—Yuki is his sister! Taro is shocked and appalled, both at Bigelow’s actions and at Yuki’s condition. It turns out that Taro and Yuki are from a noble family that conveniently ran out of money while Taro was at university in the US with Bigelow, and rather than reveal the change in their fortunes Yuki began earning money to support her brother by performing in teahouses. When that proved insufficient, she agreed to be married off by a nakoda.

Taro and Yuki are stunned to see each other. Yuki runs away, distraught at her brother’s perceived disappointment in her. For plot-related reasons, neither Bigelow nor Taro immediately follow her, so she is allowed to slip away and disappear. In her absence, Taro falls ill and dies. Bigelow promises the dying Taro that he will spare no expense in tracking down Yuki. He wanders all over Japan, Yuki wanders all over Asia, but eventually they have a heartfelt reunion at their old house in Tokyo and swear to never leave each other again.

The end!

On its own, A Japanese Nightingale is very dated reading. Is it an improvement over Madame Butterfly, which it is theorized to be a response to? I…don’t know? How are we defining “improvement” here, anyway? The happier ending with a reunited Bigelow and Yuki seems to imagine better prospects for interpersonal relationships between white Westerners and Asians (or just Japanese) than Madame Butterfly, which makes sense given Canada-born Eaton’s English father and Cantonese mother.

But much of the book feels predicated on Orientalism and appealing to Western fascination with Japan, which I guess still happens today but not in the same way as in the years immediately following the Perry Expedition. There are didactic little asides about Japanese culture and beliefs and customs, but judging from her biography Eaton never visited Japan. She was also “rebuked” by maybe the only Japanese person she actually knew, the poet Yone Noguchi, for her “masquerade” (to use the language of that linked timeline), but I don’t have the Google-fu to dig that referenced article up.

All of that said, I think it’s ridiculous to go into a book like this with the expectations and standards we have for books today. And I don’t just mean expectations about race and Strong Female Characters TM and gender relations—I mean even just the construction of the narrative itself. Authors in 1907 were writing to meet different expectations than they would be today. One of the more obvious examples of this might be the shift in narrative distance that’s come to be regarded as acceptable in third-person narration, but also things like suspension of disbelief, the role of luck and coincidence in a plot, characterization, etc. etc.

The clues about Taro and Yuki’s relationship are there for readers to pick up on, but the suspension of disbelief required to accept that plot twist is a big ask. Taro’s death makes no sense on a surface level reading (he faints and hits his head and then…wastes away from a mysterious illness?) and is equally baffling from a plot perspective, since there’s no action or realization it prompts within Bigelow. Nor would Taro’s survival have impeded Bigelow in any way in his quest to find Yuki. The whole episode feels like nothing more than a melodramatic flourish to no purpose. Omatsu, Taro and Yuki’s mother, appears for a while during Taro’s lingering Mystery Illness, and Bigelow swears to look after her like she was his own mother, but then she gets shunted off to her own parents and never appears again.

To a modern reader, all those aspects and more are enough to make A Japanese Nightingale stylistically passé, never mind how completely unappealing a character and hero Jack Bigelow is in the Year of Our Lord 2023 or whether or not the depiction of Japan and Japanese characters is ProblematicTM and if so to what extent. Even though the book was by all accounts at least moderately popular in its time (it was turned into a stage play, and then a movie), it’s so “of its time” that the appeal today is one of historical curiosity rather than rip-roaring good yarn.

Oh! This was a translation, after all. Is there anything interesting I can share about Hilda Löwenhielm?

Not really. She was a teacher and a translator and died in 1927. Never married, no children. Well, cool.

The story itself may be underwhelming, but it at least it was delivered in a singularly attractive package that can serve a much more aesthetically pleasing purpose as an objet d’art.

*Onoto Watanna, what a wonderful phrase! Onoto Watanna, it ain’t no passing craze! It means no worries for the rest of your days. It’s our problem-free philosophy: Onoto Watanna!