Every year I make a concerted effort to dig through my TBR list and the books I already own. It never outweighs the books I read from elsewhere—at this rate, I’d have to spend the next ten years reading only books the TBR to catch up on that front—but without any effort at all it’s just a graveyard of aspirations.

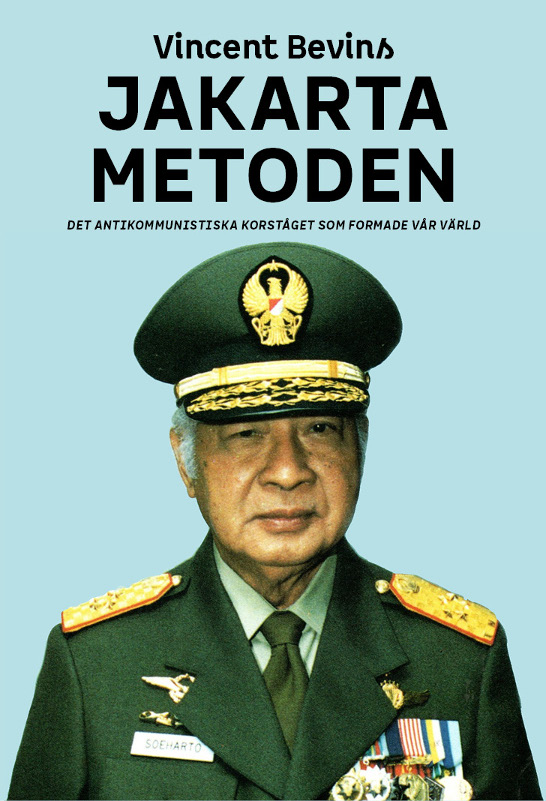

The Jarkata Method was a relatively new addition to the TBR, after I heard it mentioned several times on one of my go-to podcasts. Apparently it only made it as far as the mental TBR, though, since I don’t see it on Storygraph, but I’m counting it since it’s been on my radar since at least 2019.

I’m not the kind of reader whose review of this particular book will matter, because I’m not a historian or an expert in twentieth century geopolitics. Much of this was new to me, which I expect is largely by design within the US public education system. History more or less ended with the Vietnam War; anything afterwards was too new to be history but too old to be news. I graduated high school with an understanding that the Cold War was a thing that had happened, but not much beyond that, and I suspect that’s the case for a lot of Americans. But that was over twenty years ago. Maybe it’s finally been long enough for older headlines like Nixon, the Cold War, Reagan, and the Gulf War to be lifted out of the weird memory hole of “news” or “current events” and inducted into the pantheon of “history.” (Hard for me to say. I’m not a high school student in the Year of Our Lord 2022.) For people like me, The Jakarta Method provided a much-needed nutshell version of a slice of American history in an international context you almost never get in US history classes.

The only thing I can note is that reading a Swedish translation of an English language book on US foreign policy is a trip; more than once I found myself thinking, “But what do you know about the US, asshole?” and then remembering who the author is. It’s certainly not like I disagree with Vincent Bevins on any point he raises in the book; quite the opposite, in fact. I just have an instinctive reaction to processing commentary on American politics through the Swedish language. An article I read once (I will have to update this with a link if I find it again) described Europeans’ understanding of US politics to be something akin to a celebrity gossip rag: everyone knows the events, few people understand the context, almost no one is speaking from any kind of personal connection or insider history.

“Why did you even bother reading this in Swedish, then?” I hear you say. Because that’s what the library had available. Besides, anything in Swedish is a win for my yearly goal of 25% book consumption in Swedish.

I have no complaints about the Swedish translation of The Jakarta Method. Stefan Lindgren did a fine job, as far as I’m able to tell. Unfortunately there are at least two Stefan Lindgrens working in translation, so I can’t be sure who to thanks. I think it’s safe to credit this particular Stefan Lindgren, despite his age (wonder if I’ll still be working at 70!), since the topic matter seems to be adjacent to his other work, but he doesn’t seem particularly active these days. Who knows!