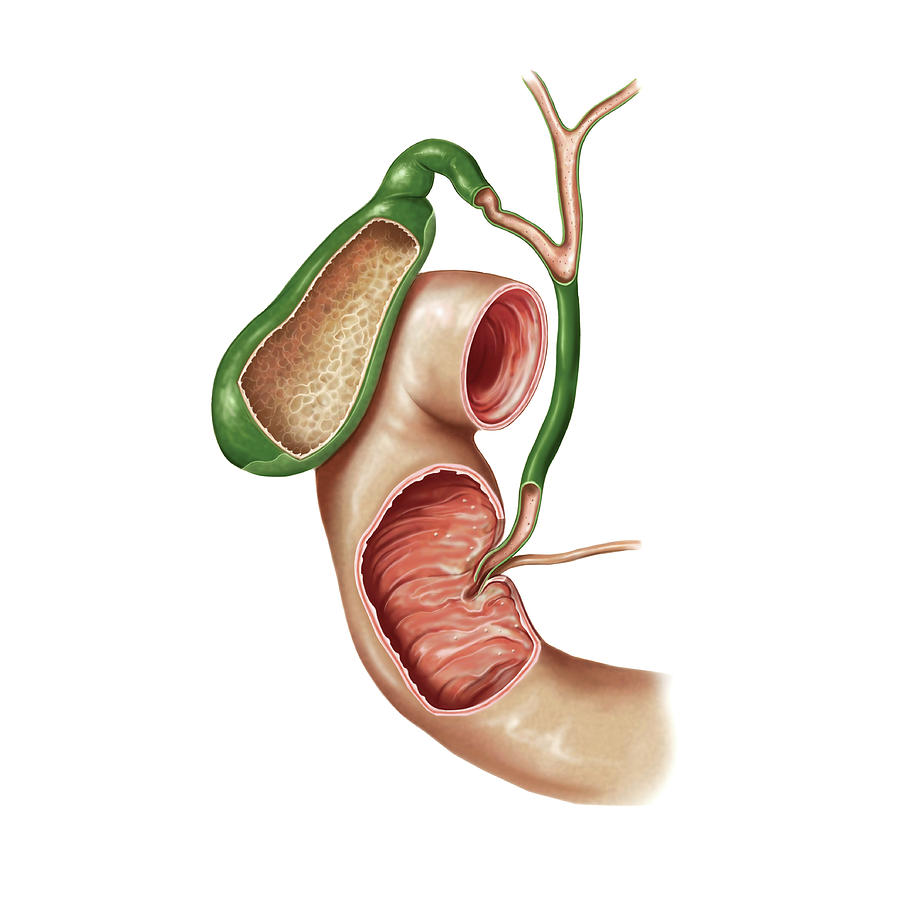

I decided to get an early start on some classic New Year’s resolutions like decluttering and ending long-term toxic relationships by having an emergency gallbladder removal two days after Christmas!

It also left me with three and a half days of nothing to do but chip away at my ebook collection; I didn’t take my purse and its ever-present paperback with me to the ER, as I fully expected to return home the same day. Well, well, well. Fortunately my phone is a miniature library of obscure and half-forgotten ebooks and I could keep myself distracted in the long waits between ultrasounds and discussions with surgeons. Most of that time was spent with the back half of Rick Berlin’s The Big Balloon (A Love Story), which up to that point I’d been reading on my morning commute.

I’m not hip to the Boston art scene, I didn’t know who Rick Berlin was before I bought the book, I’d never heard of any of his musical projects. But he put out an ad for the book on one of my go-to podcasts and since the premise sounded unique, or at least interesting, I decided to give it a try. I feel that’s only worth mentioning because someone who’s either a fan of Berlin, or familiar with his artistic milieu, will probably have a different response to it than I did.

Out of every possible Pandemic Project or Pandemic Novel, The Big Balloon is maybe the only one I can imagine that will be at all tolerable to revisit in more normal times (if we ever have more normal times). Even though the book is the direct result of COVID-19, it’s never about COVID-19. The conceit is simply this: The Big Balloon is a collection photos of items around Berlin’s home and reflections, stories and reminisces related to each item. Each little essay is entirely self-contained, with no attempt to impose chronological or thematic order on the collection (aside from organizing it into chapters based on rooms). The result is like a literary version of a Cubist portrait, where different years of Berlin’s life and different aspects of himself are presented simultaneously—or as close to simultaneously as you can get in something you read. Something about using the limitations of lockdowns to open up a vast interior world, etc. etc.

The Big Balloon worked well for commute and hospital reading because each essay was never especially long, so I could dip in and out according to subway arrivals or morphine-addled focus. And that was precisely the intended effect:

There is no linear structure to this book. No over-arching narrative. Each entry is self-contained. One piece can relate to another, but it isn’t necessary to make that connection. The reader can pick it up, crack it open anywhere, read a section and put it down. The ‘chapters’ are just the rooms in my house.

It could be said that I chose this odd-ball format for bathroom reading. For those with short attention spans. On the other hand, much as I love the twists and turns of a full blown story, the Haiku simplicity of disparate entries exposes Berlin as if opening the paper window flaps of a Twelve Days Of Christmas holiday card in no particular order.

The highly personal nature of the material also, in a way, made up for the fact that I wasn’t allowed to have any visitors. I wasn’t exactly starved for social contact generally, between the two other patients sharing my room and chatting with the nurses doing their rounds, but that’s not the same as time with your nearest and dearest in the darkest, coldest days of the year. The next best thing was Berlin plunging right to the depths of his own psyche to share with me, and the rest of his readership:

The Big Balloon is super personal. Most art, at least the art I love best, is personal. From another’s truth one extrapolates one’s own echo, wisdom, embarrassment and laughter. That’s what I’d hope for you, dear reader. That you’d laugh or at least find something self-relevant in these independent passages of my peculiar life.

A creative not-so-little undertaking that makes me want to ask the same of my friends, or save up for a dry spell on the ol’ bloggo. “Choose ten things around your house and write an essay about each one of them.” Maybe make that an additional step in the KonMari method.

Happy New Year!