I normally don’t discuss covers much, but this time I will.

The anglophone books available to me are more often than not UK editions. Sometimes there’s no difference from the US covers, sometimes there’s a huge difference, but never before have I encountered such a mood whiplash between the two.

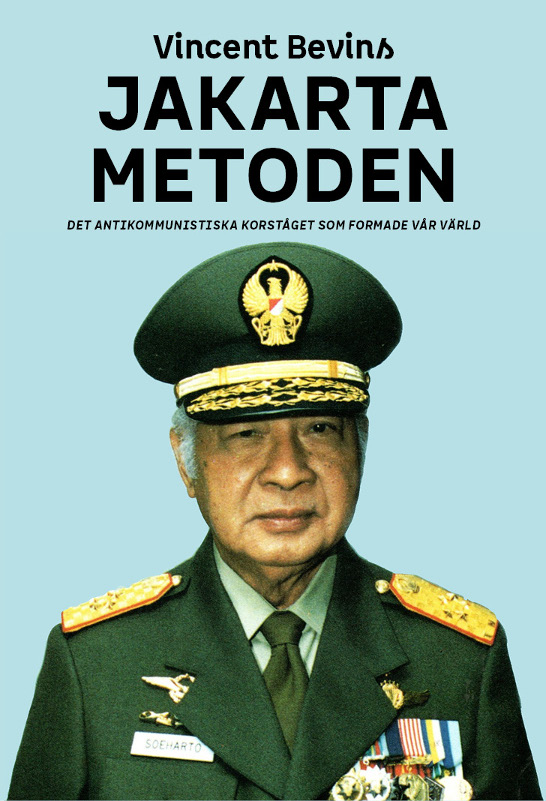

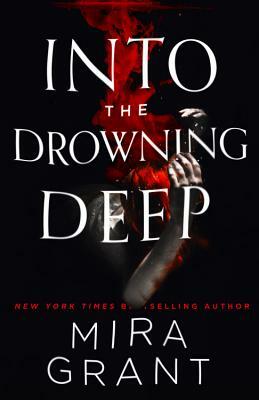

Going strictly by the cover, I would assume that we were looking at a fluffy romantic comedy in a sci-fi setting. Either that or a parallel lives kind of story, similar to My Real Children but more light-hearted. Compare that with the UK edition:

The latter more accurately encapsulates the mood of the book for me. I’m not sure what the thinking was behind the US cover, but I have a feeling that it’s probably led to a lot of disappointed readers. Is there fluffy romantic comedy hijinks? Not really! Is there a lot of grappling with the unknown and with morally repellent choices? Yes!

Is there a fair chunk of domestic violence? Also yes.

There is a lot going on in this multiverse story and my brain isn’t really built to handle those kinds of ins and outs. I’ve seen The Big Lebowski I don’t know how many times at this point, and I still can’t string together the chain of events surrounding Bunny’s disappearance, the ransom note, and her reappearance without sitting down and drawing a lot of diagrams and timelines. And that’s a story where the intrigue is just the background plot for brilliantly executed scenes and snippets of dialogue—in The Space Between Worlds the intrigue is basically the entire story.

Guess I need to adhere to a stricter drug regimen to keep my mind even more limber.

Getting back to The Space Between Worlds, all of this is potentially a Me problem and not a Book problem. In addition to my troubled relationship with intrigue, I also took a break from the book for almost a whole week, which couldn’t have helped. Keeping track of the different multiverse versions of characters wasn’t necessarily the hard part, but keeping track of all the different Earths and their politics was a lost cause for my addled brain. Earth 0 is the prime, principal Earth on which the bulk of the intrigue plays out, but events on Earths 22 and 175 are also important. Not to mention I think there’s a third Earth that our traverser protagonist Cara visits, but I don’t think it had much to do with the actual plot.

Likewise there are some world-building elements that were not really laid out cleanly for my addled brain, or that were introduced way too late in the story, or that maybe I just happened to skim over. Unfortunately those elements are kind of plot-essential, so from a technical standpoint I wish they had been made clearer earlier on in the story. (Assuming that I just didn’t miss them, which I totally might have!)

But I was able to overlook all of that because I could see that the point for Johnson wasn’t “wow multiverses sure are cool.” Instead, it was more “how would multiverse traveling get integrated into the world as we experience today” and “how can the idea of parallel lives and parallel selves be used as a metaphor for Real Life Stuff,” and I was along for that ride. It seems, judging by other reviews, that some people weren’t along for that ride. And that’s okay! But since one of my own paradigms for years has been the idea of alternate universe versions of myself, Johnson’s take on the multiverse was a lot of fun for me.