At least 48 books:

I made to 51 thanks to a long-haul flight and two weeks of Christmas vacation. Success!

At least 4 are in French:

Trois femmes puissantes

En attendant la montée des eaux

Terre des hommes

Rien ou poser sa tete

Made it!

At least 25% are in Swedish:

By the skin of my teeth, due to a glut of English books over the holidays. Though, my total foreign language books (as in, Swedish and French combined) is close to 40%.

At least 12 are non-fiction:

Sister Outsider

The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism

The Lies That Bind

Hemlös—med egna ord

How to Be an Anti-Capitalist in the 21st Century

Wind, Sand and Stars

The House of the Dead

Letters to a Young Poet

Conflict is Not Abuse

Journey to Russia

Artful Sentences: Syntax as Style

Burnout: The Emotional Experience of Political Defeat

Rien ou poser sa tete

Hellenistic Astrology: The Study of Fate and Fortune

Filosofins tröst

Fat Talk Nation: The Human Costs of America’s War on Fat

With Burnout, I hit my non-fiction goal by September. Hooray!

At least 10 have been in my library for over a year:*

Wind, Sand and Stars

The House of the Dead

Hellenistic Astrology: The Study of Fate and Fortune

Tordyveln flyger i skymningen

Even moving the goal posts back to 10 books, I failed this one by every possible measure. It was inevitable; I made such substantial progress on this in the last few years that I began to run out of books that I hadn’t already read but that still looked interesting. Even if I count ebooks, that only gets to five. We’ll see what 2026 brings.

At least 10 have come from my TBR (as of January 1, 2025):

The Idiot

An Unnecessary Woman

En attendant la montée des eaux**

Om det regnar i Ahvaz

Conflict is not Abuse***

Artful Sentences: Syntax as Style

Burnout: The Emotional Experience of Political Defeat

Hellenistic Astrology: The Study of Fate and Fortune

Tordyveln flyger i skymningen

Three Apples Fell From the Sky

Filosofins tröst

Fat Talk Nation

Dietland

Gabi, a Girl in Pieces

Årsboken

Success! Surpassed even an ambitious book-a-month goal of 12! But let’s not reflect on how many books I added to my TBR…

At least half are by women or enby authors:

Excluding anthologies with mixed genders, 22 books were by women and 20 were by men. On target.

At least 10% are by Black authors:

Trois femmes puissantes

Sister Outsider

En attendant la montée des eaux

The Lies That Bind

I never found a fifth book. Hopefully the coming issues of Karavan will have some good recommendations for me there.

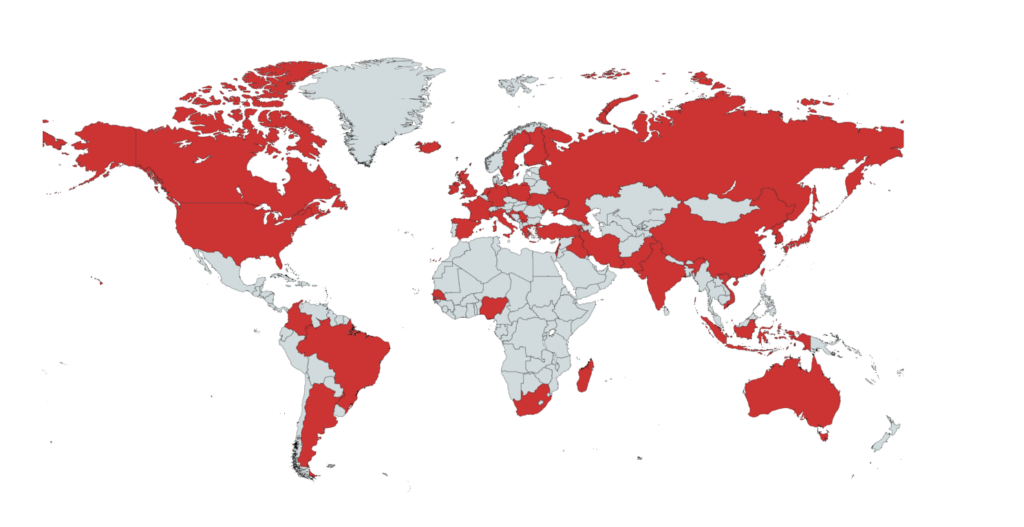

At least 1 new-to-me country (as of January 1, 2025):

Lebanon (An Unnecessary Woman)

Iran (Den blinda ugglan)

Guadeloupe (En attendant la montée des eaux)***

Croatia (Journey to Russia)

Serbia (Encyclopedia of the Dead)

Ukraine (Döden och pingvinen)

Armenia (Three Apples Fell From the Sky)

Taiwan (Notes of a Crocodile)

Blew this one out of the water. Maybe it was too easy? It certainly helps to have an international WhatsApp book club.

*I revised this one after I didn’t quite meet it last year. Is it shifting goalposts or is it adjusting targets to better correspond to reality? You decide!

**Technically I had added another Condé novel to my TBR instead of this one. Since I mostly just picked it at random to act as a Condé placeholder, I’m counting En attendant… as part of this goal fulfillment.

***As with Condé, I had another Sarah Schulman book on my TBR (Gentrification of the Mind). But Conflict is not Abuse left such a weird taste in my mouth that I feel confident taking Gentrification off the TBR. It also seems like Conflict rehashes, at least in passing, the main points she made in Gentrification.

****Guadeloupe is an overseas department and region of France, but it feels like it should count.