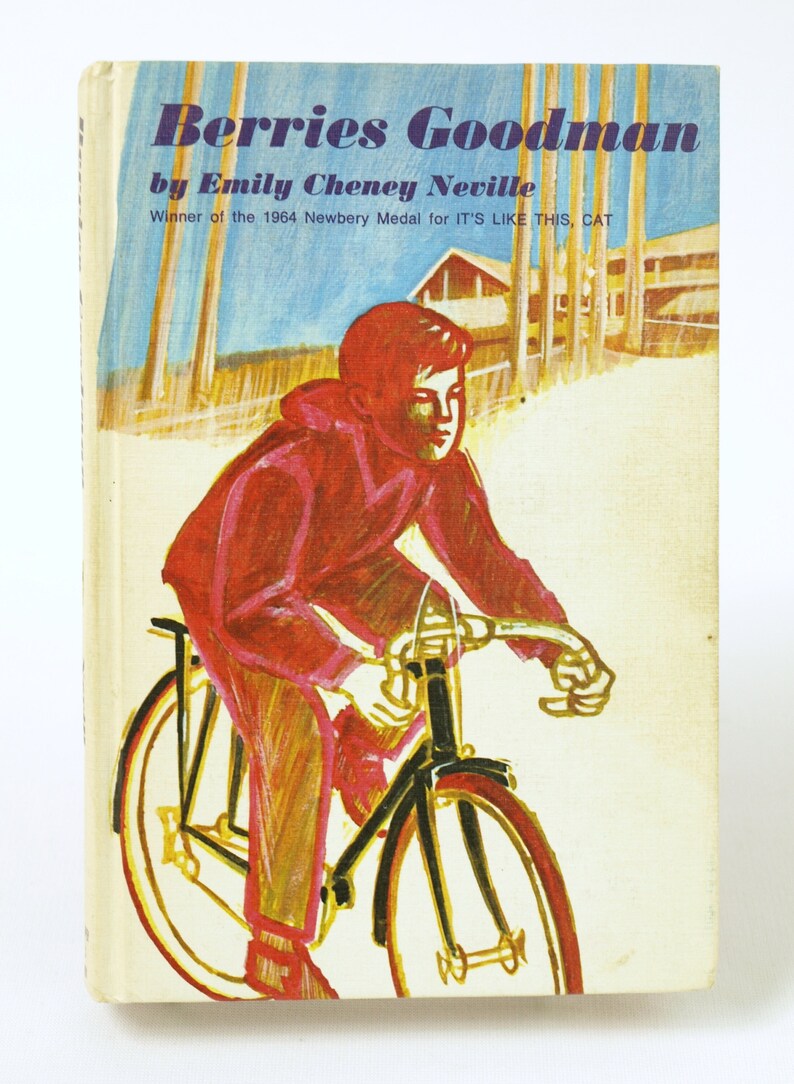

Like Emil and the Detectives, Emily Cheney Neville’s Berries Goodman was another parental library inheritance that was always just around the house, never fully absorbed either into my books or my brothers’. It made for a nice break from dusting bookshelves, as it turned out.

We start off in a conversation between teenage Bertrand “Berries” Goodman and his childhood friend Sidney Fine, who Berries hasn’t seen since he moved out of the fictional suburbs of Olcott Corners to New York City. Sidney is playing truant and heading off to New Jersey for the day, for reasons unknown, and has called on Berries in New York for help and to catch up.

Then we flash back to one year in Berries’ and Sidney’s elementary school lives, right after the Goodmans’ relocation to Olcott Corners from New York. Berries quickly befriends Sidney, while jokes and comments from the adults around him make it clear that there is a not-so-subtle strain of anti-Semitism in the neighborhood. When other children, like Berries’ neighbor and frenemy Sandy, repeat similar talking points, Berries reacts in anger and confusion: anger at the insult to his friends (and by now it’s no spoiler that this includes Sidney as well as his friends back in New York) and confusion over the fact that anyone would even believe such stupid things. Everything comes to a head when the trio go ice skating and the bossy but well-meaning Sandy dares Sidney into a stunt that leaves him hospitalized. Sidney’s mother fears that the latent anti-Semitic attitudes are going to start escalating and pulls him out of their school in favor of the school in the nearby Jewish neighborhood and forbids Sidney from playing with Berries. For a while the two meet in secret, but after their fathers catch them out, they’re separated for good.

Not long after, Mrs. Goodman decides she’s tired of the suburban life and the Goodmans move back to New York. Years later this is where we catch up with teenage Berries and Sidney, who is trying to get a bus out of the Port Authority. Berries goes with Sidney back to Olcott Corners and things are eventually smoothed out between the two families.

The condensed version sounds like an anvilicious after-school special because I left out all of the slice-of-life incidentals. Everything in the actual book unfolds more carefully and casually than that and is interspersed with nostalgic unsupervised kids in suburbia shenanigans, and rather clear-eyed observations and criticisms of middle class American standards and parenting.

There’s an interesting comparison to be made just by looking at the difference in covers between Berries Goodman and another one of Neville’s young adult novels, It’s Like This, Cat. There are essentially two different covers for Berries Goodman, neither of which have been updated at all.

Meanwhile, It’s Like This, Cat seems to have been continuously updated and repackaged for a new readership.

It’s Like This, Cat was on reading lists in my school years. I saw it in the library. But the only time I’ve ever seen Berries Goodman is in my shelves at home. Of course, I haven’t read Cat so I can’t make the comparison or even begin to guess at why that one has remained so popular and Berries hasn’t. But if you happen to stumble across Berries Goodman, you should pick it up. It’s a fun read and Neville has a fantastic ear for dialogue, especially between kids.