I’m already behind in my reading (result of reading several good books at once, not to mention a handful of magazines). Time for a filler post! Incidentally, I also realized that I’ve never really been explicit about what my reading goals are, so maybe it’s just as well I talk about them for once.

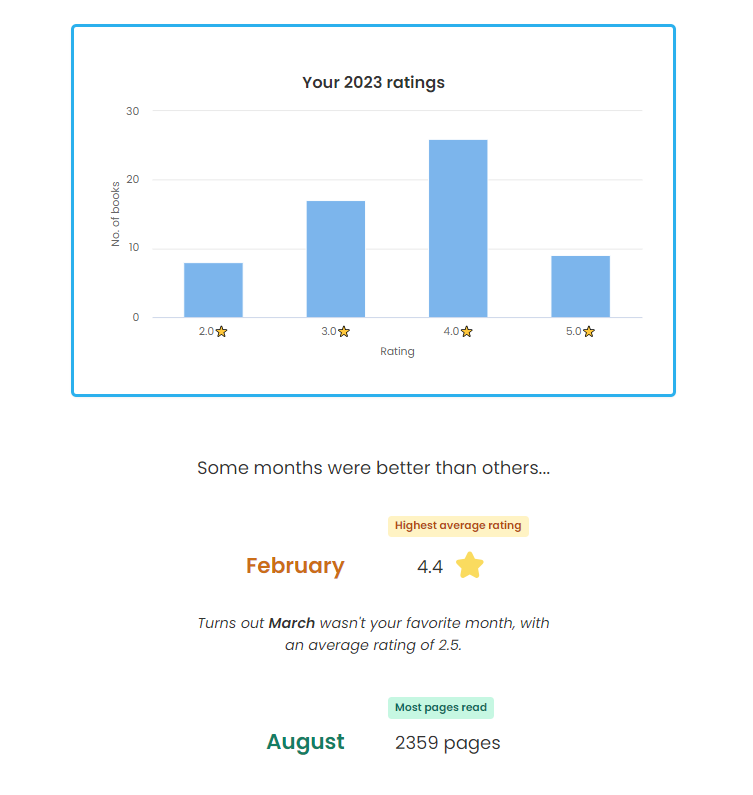

Numbers

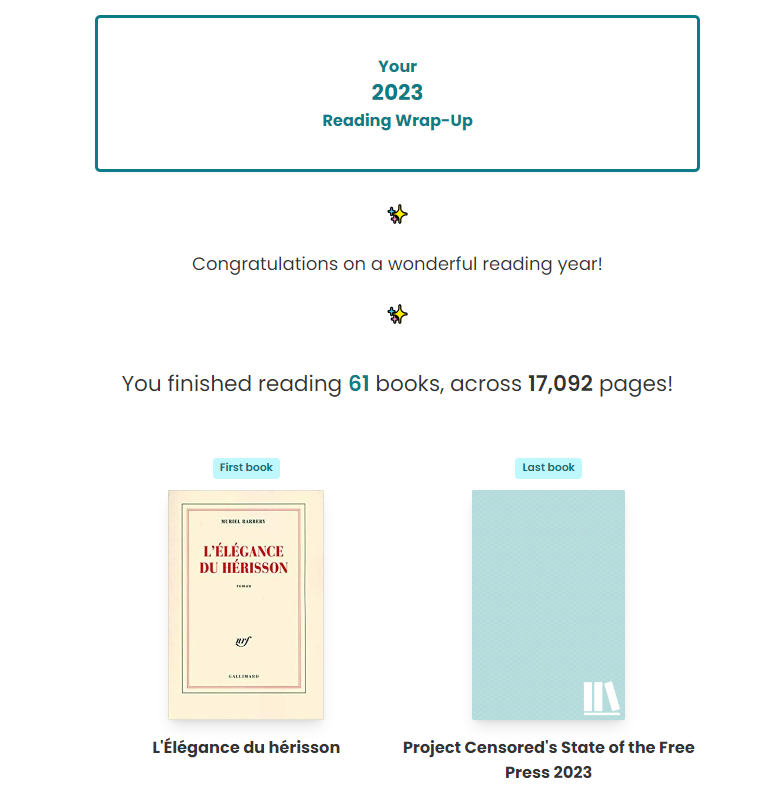

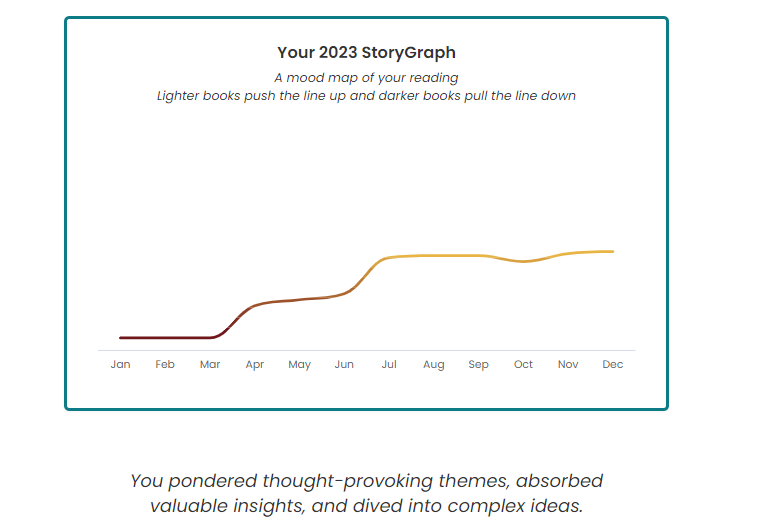

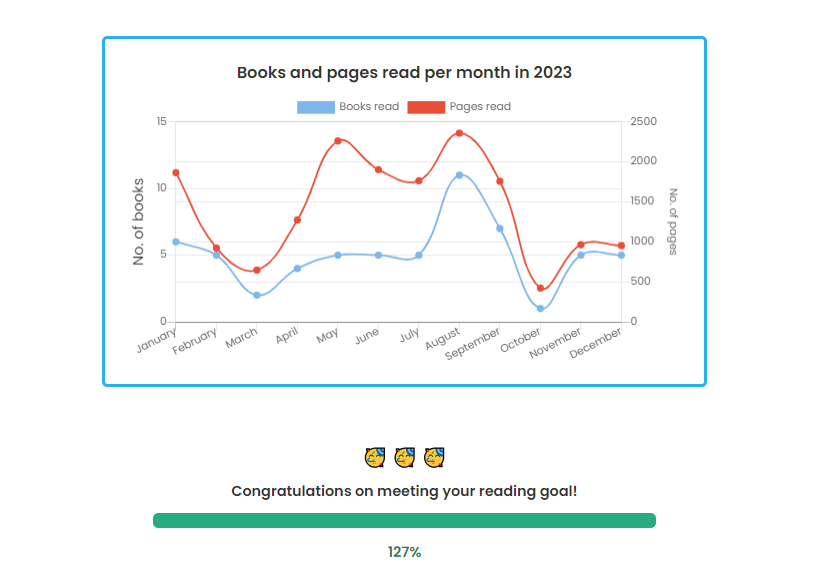

First and foremost is just the total number of books. I’ve settled on 48 books per year for a while now and it seems to be a good and reasonable goal for me. I end up hitting it pretty comfortably, with an early surplus some years and a mad last-minute holiday reading binge in others. It’s a number that ensures that I’m reading regularly, and regular consumption of books is really important for keeping my mood up—especially in the winter, when everything skews naturally towards depression and darkness.

Language

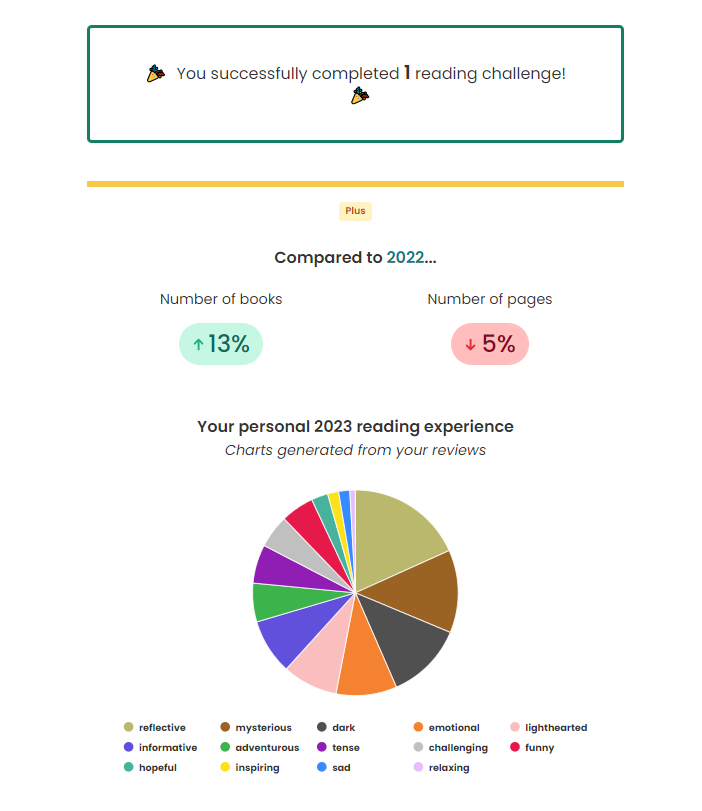

I also try to make sure that a certain percentage (25%) of my reading is in Swedish. This figure got a bit gnarly once I decided to introduce French into the mix as well. Was it important for that 25% to be Swedish? Or was it enough to just be not English? I haven’t decided yet. But so far I’ve been pretty good about hitting that threshold. I think I’ve met it every year since I decided to start keeping track.

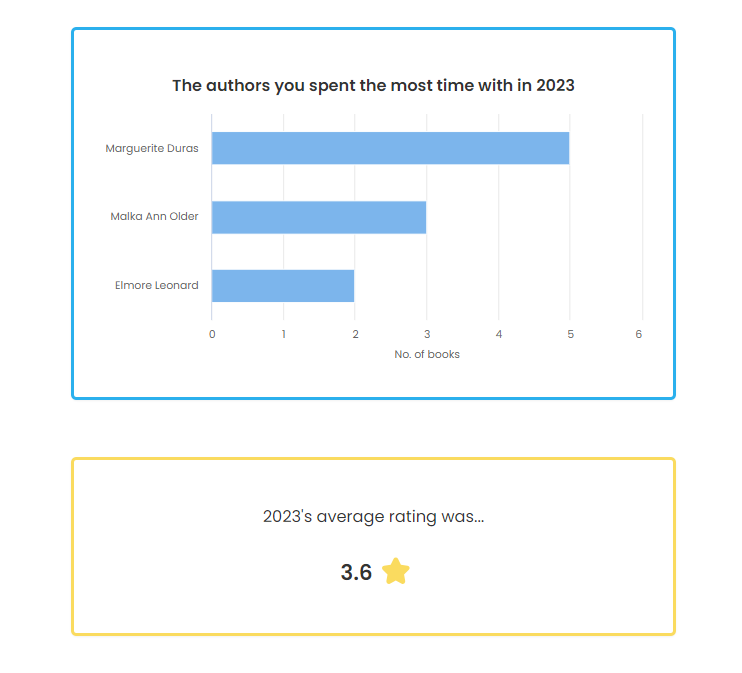

My French consumption, on the other hand, is dictated by a fixed number of books per year, mostly because I can’t read French as fluently. Do I meet this goal as consistently as with Swedish? Absolutely not! Out of the last four or five years, I only met it for the first time in 2023. Big ups to Marguerite Duras for that.

Content

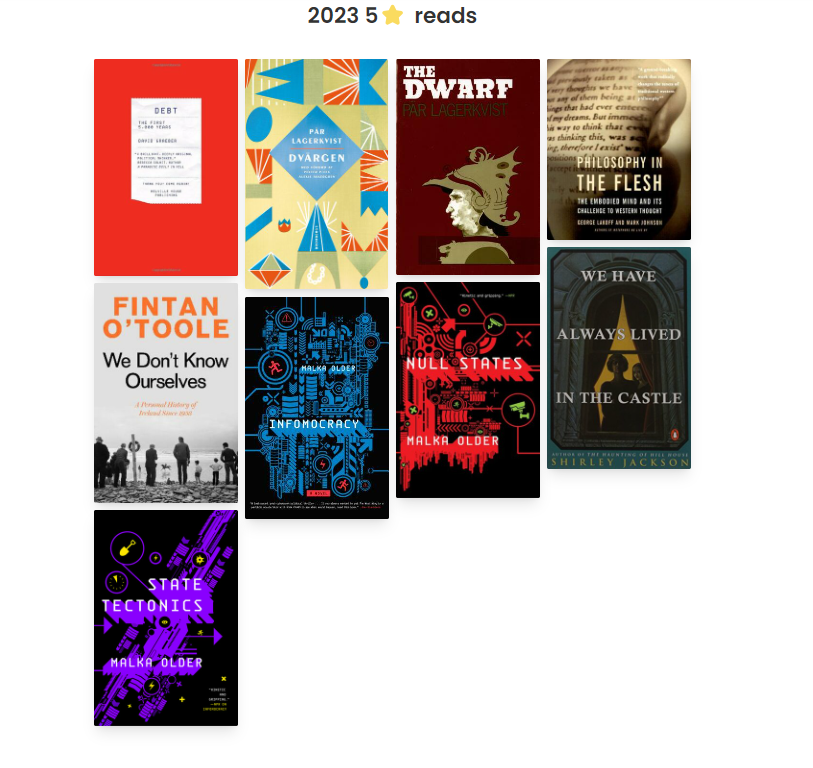

One of my earliest grown-up life book goals, in addition to working my way through the TIME Top 100 Novels of All Time list, was one non-fiction book a month. Novels are great, but there’s a particular itch that only non-fiction can scratch. I’ve stopped making a deliberate point of this target, but a cursory glance through my Storygraph statistics suggests that I accumulate at least twelve non-fiction books per year basically automatically at this point.

Beyond that, I don’t have any genre or topic matter goals. What I’ve tried to do recently is to lump books about roughly the same topic together concurrently, so for example as I’m re-reading my AP European History textbook, I dip out of chapters and into other books that examine the historical periods in question (The Dawn of Everything, Caliban and the Witch, A Lenape Among the Quakers). Reinforcing the names and events is good, and the switch in perspectives and shift in focus helps paint a more complete picture of the topic in question.

I’m also not counting specific study guides or resources that I read in order to achieve other goals, meaning that I don’t need to make it a goal to read books like Essential legal English in context : understanding the vocabulary of US law and government because they’ll get picked up along the way to other destinations.

Identities

Uh oh, identity politics! Whatever.

Unsurprisingly, back when the TIME Top 100 Novels list was my primary roadmap, my reading skewed really heavily towards men, and white men at that. Several years of participating in the Austin Feminist Sci Fi Book Club (RIP) means that now the gender split in my reading is pretty equitable. To some extent, I think that torch has been passed on to the literary magazine Karavan, as most of the books I have read so far based on reviews or interviews there have been by women. (Not all, but most.) At one point I had to make a deliberate point to reach gender parity in my reading, but it seems now that gender parity, like my non-fiction consumption, happens automatically.

The larger umbrella of queer authors also turns up a lot thanks to the Austin Feminist Sci Fi Book Club; however, that’s a tricky statistic to count because it relies on the author being out, and for a number of reasons authors might not want to be that public about their personal lives and information. I don’t think a fixed number is a good metric in this case, so the hazy concept of “awareness” will have to do.

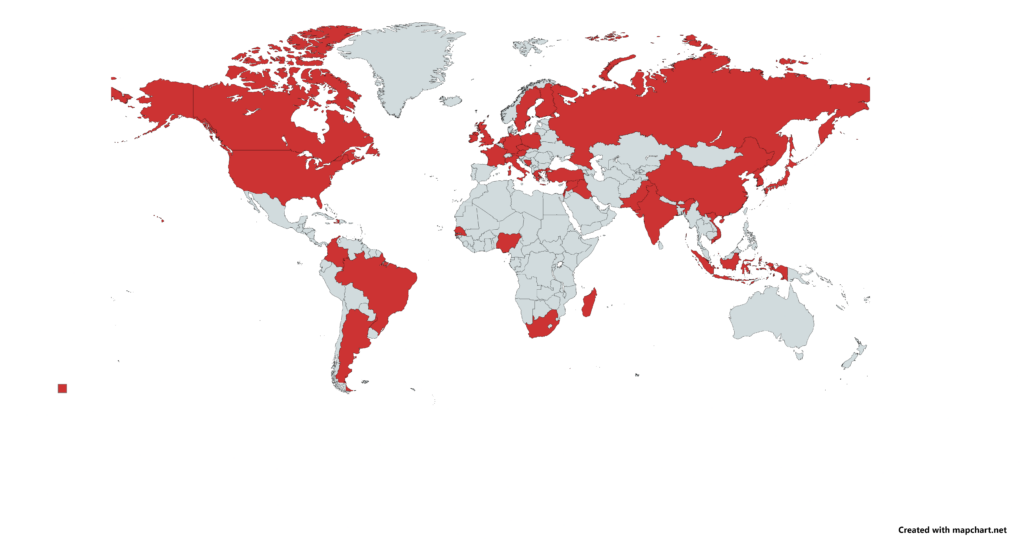

Ethnicity and race is, if possible, stickier wicket, in part because of the overlap with geography. The two easiest filters I think about are 1) where authors are from, and 2) whether they’re from the dominant culture (class, ethnic, religious, racial, etc.) in that place. Again, hard to pin a number on this: is it perfectly logical and consistent for me, a white American, to use US census data to evaluate my reading because that’s the context of most of my upbringing and the source of my biases and errors in judgment? Or is it inappropriate to think about world population in terms of US categories and breakdowns?

However way you slice that, though, left unattended my reading list skews very heavily White and if there’s any active guiding principle to my reading at the moment, it’s that.

Location, location, location

The above identity discussion segues nicely into a slightly more concrete, quantifiable framework in consideration of filter number one: where are authors from? The pin-in-the-map model. Those pins would be pretty heavily concentrated in some parts of the world and few and far between in others. Once again Karavan to the rescue, with its focus on Latin American, African, and Asian literature in translation. Asymptote is also worth noting here; the problem is not the quality of their recommendations but my lack of follow-through on what I discover there. Now that reading for the Austin Feminist Sci Fi Book Club will naturally be winding down, it leaves room for me to fill my time with recommendations from various literary magazines. My long-term project? A pin in every country on the map. One new country annually seems like a start.

Declutter

Another goal I’ve habitually set for myself is to read a particular number of books that I’ve owned for at least one year. This will never stem the flow of new books into my library, but without a concerted effort at releasing some back into the wild they will accumulate at a rather alarming pace. And there are good things in my library that deserve to be enjoyed! Treasures like vintage short stories collections from my Dede or one of the local thrift stores. Sometimes what you’re looking for is right in front of your face.

I used to set the goal at just one book, then increase it incrementally: two books, then three, then five, then eight… (Fibonacci numbers are fun). Now I can track this through challenges on Storygraph. Last year I hit my goal of twelve, and this year I’ll aspire for the same.

Similarly, I’ve tried to actually chip away at my “to-read” list instead of just using it as a catch-all for anything that sounds even remotely interesting. I balance this with periodically reviewing the list and removing anything that no longer interests me, but even so it’s at well over 500 books by this point. That’s ten years of reading for me, assuming I never read anything new. I read seven of those books in 2023; I’ll try for a nice round ten in 2024.

Conclusion

So what do my reading goals for 2024 actually look like? In a nutshell, with bullet points?

At least 48 books, of which:

at least 4 are in French, and

at least 25% are in Swedish

at least 12 are non-fiction

at least 12 have been in my library for over a year

at least 10 have come from my to-read list (as of January 1, 2024)

at least half are by women or enby authors

at least 10% are by Black authors

at least 1 new-to-me country (as of January 1, 2024)

I look forward to returning to this post in December and seeing how I did!