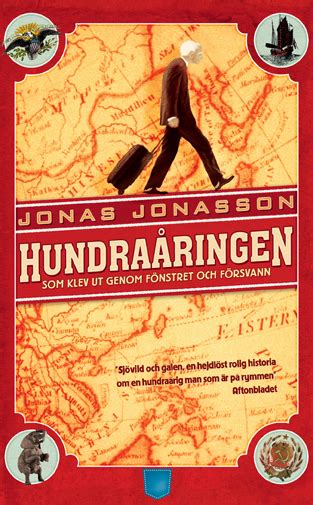

Jonas Jonasson’s novels are hard to miss in Sweden, with their striking and consistent titles and cover designs. Yet at the same time they’re nearly invisible, fading into the background, precisely because they’re everywhere: the books that everyone’s read, to the point where it feels not at all urgent because at this point you’ll pick it up via cultural osmosis. So I never gave much thought to Hundraåringen beyond rescuing it from the junk pile at a friend’s apartment just to have it around—just in case—but promptly forgot about it, except to periodically confuse it with A Man Called Ove. What finally got me to pick it up was 1) a personal recommendation from a friend and 2) its appearance as Sweden’s entry in the EuroVision book contest.

“Finally, we’re releasing more than Nordic noir into the world,” I thought.

An SFI classmate years ago described Hundraåringen to me as “a Swedish Forrest Gump” and that just about covers it: 100-year-old Allan, as the title suggests, climbs out the window of his room at the senior home on the morning of his birthday because he’s just utterly fed up with living there. (If I’m reading later subtext correctly, it’s more an act of depression than adventure.) Things start happening as soon as he encounters a young man with a suitcase at the nearest bus station, and the adventure afterwards is interspersed with his life story, which is filled with some of the most significant events and people of the twentieth century. There Allan is in the margins of the Spanish civil war, the development of the atomic bomb, the downfall of the Soviet Union, and on and on it goes. Throughout all of this, Allan is phlegmatic and unflappable, escaping from political prisons and dispatching would-be criminals with fatalistic indifference.

Jonasson is careful—or thorough, maybe, is the better word?—to make use of every detail so that simple gags become essential plot elements. These moments would fall flat in a more serious or melodramatic story, and feel like deus ex machina, but because the whole story is farcical from beginning to end it instead becomes just a more elaborate joke, elevated from physical comedy to long-form setup and payoff.

From a translation perspective there are a couple words and jokes that I’m curious to see handled in English, so of course now I have to read it again in English. But by all accounts it seems to land well with English speaking readers.