Here’s the rare “book off the TBR” win! Of course, Debt: The First 5,000 Years was a relevantly recent TBR addition that has not undergone the shameful, years-long limbo that other titles have, but any progress is progress.

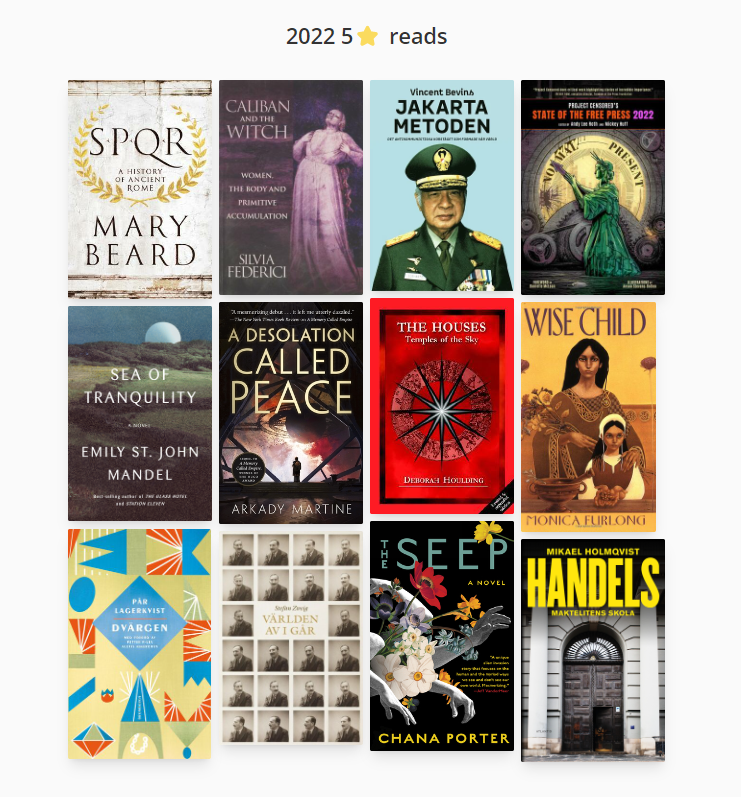

If you look back at the non-fiction I read in 2022 (especially the non-fiction I read and enjoyed in 2022), you can see something of a common denominator:

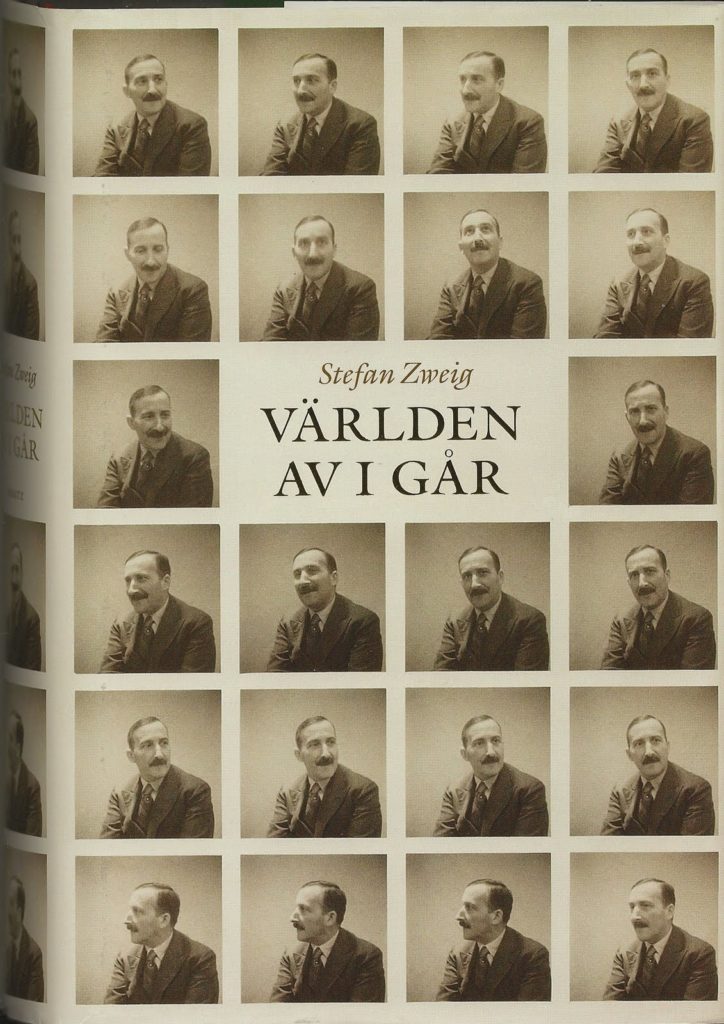

Caliban and the Witch, Jakartametoden and Handels: Maktelitens Skola all go a very long way towards explaining how capitalism as we know it came to be and how its current norms and structure are maintained. Project Censored’s State of the Free Press 2022 is reportage often aimed at critiquing those norms and structure and, if you want to stretch the conceit, ancient Rome is where we like to start the story of Europe, and it is Europe from which springs everything else the other selections touch on. (Temples of the Sky is the odd one out, a niche hobby read.)

Whether this trend is due to the natural progression of my interests, the years I’ve now spent absorbed in financial reports, the turbulent times we live in, or some other constellation of factors, who can say. Regardless, it continued straight away into 2022 with Debt.

I’m not lucid enough a thinker to provide a pat nutshell summary of my own, so I’ll lift the one on the book’s Archive.org page:

[Debt] explores the historical relationship of debt with social institutions such as barter, marriage, friendship, slavery, law, religion, war and government; in short, much of the fabric of human life in society. It draws on the history and anthropology of a number of civilizations, large and small, from the first known records of debt from Sumer, in 3500 BC until the present.

And then the one from the back of the book itself:

Before there was money, there was debt. For more than 5,000 years, since the beginnings of the first agrarian empires, humans have used elaborate credit systems to buy and sell goods—that is, long before the invention of coins or cash. It is in this era that we also first encounter a society divided into debtors and creditors—which lives on in full force to this day.

So says anthropologist David Graeber in a stunning reversal of conventional wisdom. He shows that arguments about debt and debt forgiveness have been at the center of political debates from Renaissance Italy to Imperial China, as well as sparking innumerable insurrections. He also brilliantly demonstrates that the language of the ancient works of law and religion (words like “guilt,” “sin,” and “redemption”) derive in large part from ancient debates about debt, and shape even our most basic ideas of right and wrong.

We are still fighting these battles today.

This is the best kind of nonfiction: written by a knowledgeable academic for a lay audience without insulting their intelligence or devolving into jargon and obscure terminology, with a heaping helping of works cited at the end.

In many ways, this is the less crackpot-y, more grounded and more academic answer to Sacred Economics, which I read a few years ago and which helped keep me oriented in Debt. A lot of what Eisenstein describes as “gifts” seems to overlap with what Graeber describes as the favors that, with the advent of currency, turn into debt. Neither of them mention each other, however. Both books came out in 2011*, so I’m not sure whether it’s Graeber or Eisenstein who should be referring to the other. (Graeber might have felt that Eisenstein wasn’t nearly academically rigorous enough to cite and too out-there to be worth engaging with otherwise, and I can’t say I would have blamed him.) They definitely draw from at least a few of the same sources, such as Marcel Mauss.

I expect I will end up re-reading it later in the year, as it’s so dense with information and argumentation that there’s no way you can absorb it all at once. (Maybe you can. I can’t.) For now, time to give my brain a bit of a break.

*I think. It’s hard to tell, precisely, with Sacred Economics beyond “before 2012.”