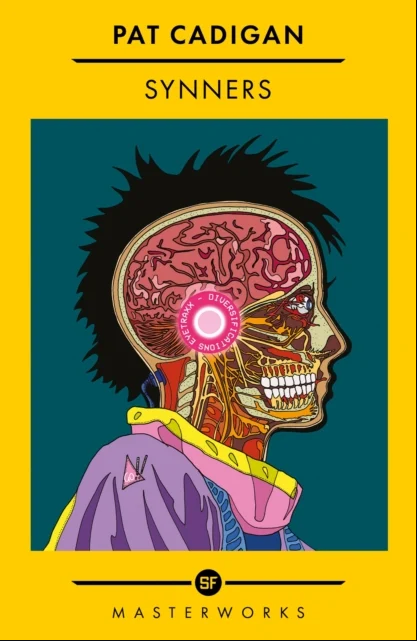

A chapter out of Pat Cadigan’s Synners appeared in Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture, and I enjoyed it so much I decided to read the whole book.

The whole book, it turns out, is a bit of a tome: 496 pages of a tome, to be exact. That’s a full two hundred pages longer than Neuromancer, its cyberpunk partner-in-crime and most apt comparison. Can the center hold?

For me, I’m not so sure. There’s a lot going on in Synners and I’m not even sure what happened.

We have Visual Mark and Gina, two music video creators working for a corporate behemoth called Diversifications, Inc. after their scrappy little independent studio was sucked up in a merger. We have Gabe, an adman also working for Diversifications, Inc., who is addicted to playing hyper-immersive video games (think Star Trek holodeck style) and the company of two AI? imaginary? personalities. We have Sam, Gabe’s estranged and emancipated teenage daughter and wunderkind hacker, returning to LA from a retreat in the Ozarks after receiving a mysterious data dump from her hacker friend Keely. That information, it turns out, is high-level top-secret corporate espionage material from Diversifications, Inc. pertaining to the next product they’re getting ready to launch: sockets that will allow people to connect to the Internet directly from their brains (Neuralink, essentially). The sockets work well enough…at first. Then crisis hits and Gina, Gabe, and Sam have to team up in virtual reality to halt the march of a deadly stroke-inducing virus.

I’m pretty sure that’s what I read, anyway.

In between those important plot points is a lot of stage setting to build the atmosphere of Retrofuturistic Cyberpunk LA, which I’m sure hit a lot different in 1991 than it does now.

This is where I’m of two minds. Cadigan has the imagination as well as the work ethic to really build a fantastic and immersive world that’s fun to spend time in, but the actual plot spends a lot of time stumbling around. The initial pacing of everything had me expecting a story about how our ragtag group of heroes would hack the planet, expose the corporate greed and malfeasance at Diversifications, Inc., and send the bad guys to jail. But then somewhere around the halfway? two-thirds? mark, Diversifications, Inc. wins their much-needed approval from the Food, Drug, and Software Administration and the sockets become a fait accompli. Okay, well, now what?

If deus ex machina is the name for a pat and unsatisfying solution to a plot problem, what’s the name for a pat and unsatisfying problem introduced into a story to drag it out? The deus ex machina problem here is the virtual reality stroke virus: its connection to everything that happened before is tenuous at best, which makes the final climactic fight? showdown? feel slapped on and irrelevant. This is the stuff that seems most interesting to Cadigan, and she could have started everything right after the introduction of the sockets to slow burn the tension through growing numbers of unexplained deaths until we arrive at the existentialist showdown with the source of it all. So why didn’t she?

Synners was published in 1991. If I’m inferring correctly from Cadigan’s dedication, it was more of a “long time coming” novel than a “frantic and immediate burst of genius” novel, and that tracks with just how much The 80s come through in the story. It’s like a cross between MTV, the Sprawl trilogy, and a romcom, all in a Clockwork Orange-level patois.

Positive reviews from recent years enthusiastically declaim Cadigan’s vision of the future as “spot on” but you really have to squint to get Cadigan’s ideas and our world today to line up. People in Synners are still walking around with offline camcorders and connecting to the Internet through physical landlines; music videos, of all things, have gained primary cultural import; their online world has that distinctly visual/spatial paradigm the 80s futurists assumed things would take, with goggles and sensor suits and the like. It’s all extremely dated.

Of course, if you tilt your head sideways you can reinterpret music videos as the omnipresent video content on places like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube, and people like Visual Mark and Gina as a kind of influencer, but even then it’s an unsatisfying fit because the ultimate climax of the book comes down to the naïve chestnut of But What Does It Mean To Be Human When You’re A Machine. Mark and Gina’s relationship to their audience, and even to the videos they create, isn’t really a topic of concern or at all relevant to the plot. The condensation of online content ownership and delivery into a small number of huge corporate overlords is the one thing that maps pretty neatly on to today, but it’s not much more than background radiation, the inciting incident that kicks off the actual plot.

Much as I love the spirit of linguistic playfulness in the slang throughout Synners, it did a lot to get in the way of the book for me. Not only in understanding what was happening, or what characters meant, but also in just enjoying the book. What’s fresh and exhilarating in a single chapter (in, for example, an anthology like Flame Wars) is exhausting to keep up for close to five hundred pages. For all of Cadigan’s focus on music, and groove, and rhythm, the language itself is often choppy and awkward. Even (tragically) in dialogue, where flow and sound is especially important. Or puns or slang that feel like a stretch. “Synner,” for one, short for “synthesizer,” as in people like Gina and Visual Mark: that one is just too cutesy and too much of a reach to really land for me.

All of that said, this is the rare book I can understand reading again. Going into things a second time, with foreknowledge about the shape of things to come, could well be a better experience than the first time around.