One of the last books I finished in 2021 (a record reading year for me, though maybe not for entirely good reasons) was Black God’s Kiss, a selection for the Austin Feminist Sci Fi Book Club’s January meeting.

Or, well. To be more precise, the short story “Shambleau” by C. L. Moore was a selection for the meeting. Beyond that, we were left to our own devices to find what we could of Moore’s writing elsewhere. The Stockholm public library had Black God’s Kiss, a 2007 edition of the anthology of Moore’s “Jirel of Joiry” that Paizo first collected and published in the 80s, so I rounded out my sci-fi experience with a generous helping of fantasy.

I won’t comment too much on “Shambleau” here, because it’s not in the Black God’s Kiss collection, but you can easily find it in the Internet Archive’s fantastic collection of old pulp magazines. That said, the protagonist of “Shambleau,” Northwest Smith, appeared in several other stories by Moore, including a crossover story with Jirel of Joiry that does appear in this collection.

To provide some context, our organizers suggested C. L. Moore after doing a deep dive into the real-life pulp writers who inspired the writer characters in the Star Trek: Deep Space 9 episode “Far Beyond the Stars.” There is widespread fan agreement (and maybe even official Word of God?) that the character Kay Eaton is a fictional analogue for Star Trek writer and producer D. C. Fontana as well as pulp writer C. L. Moore. (That said, while Eaton in the episode is instructed not to disclose her gender, there’s nothing in either Moore’s or Fontana’s biography indicating they did likewise. Moore used initials to hide her identity, but that was to hide her status as a published author from her employer, not necessarily to obfuscate her gender.) That was the first time I’d ever heard of Moore so this was undiscovered country (hah! hah!) for me, and I think most, if not all, of our book club members.

Up to this point I’d already read several short stories from the magazines in question—primarily Weird Tales, but also a few others like Astounding Stories—so I was familiar with their typical literary style. I bring this up because Moore writes in the same style and thus her stories have a certain breathless “biff! pow! socko!” quality to it that’s no longer en vogue. And like so many of these other stories, the characters are really second billing to the Weird and Astounding elements: the alien settings, the supernatural forces, the fantastic magic. Does Jirel really evolve in the way we expect characters to do today? Only very slightly, perhaps, in the title story. Do we get a glimpse into her inner life, thoughts, dreams? Not really. Does she have any defining characteristics besides “proud” and “violent”? Nope! It’s not entirely science fiction or fantasy as it’s commonly written today, but if you’re already well-read in the genre then Moore does not disappoint. The stories advance at a breakneck pace through the weird and magical 16th century France that Moore has created, the kind featured in countless Dungeons & Dragons campaigns.

The collection is entirely short stories. While the first two are tied together through their plot, and a couple of the later stories make oblique reference to the events of the first, all of the stories stand on their own and exist in a sort of self-contained vacuum. This only makes sense, when you consider their original publication over several years in various editions of various magazines, but readers going in expecting (for whatever reason) a long-form novel would be confused and possibly disappointed. Even with that understanding, it can take a moment to shift gears when you’re mostly used to reading novels, or short story anthologies where the stories are entirely disconnected in terms of plot and characters.

From a genre historical perspective, these were a lot of fun. After countless words spilled about Manly He-Man Heroes running around beating stuff up, having a Xena Warrior Princess run around and beat stuff up is a welcome change. One refreshing difference from stories we see today is that Moore never presents it as weird or unusual for Jirel to be the feudal head of Joiry or the commander of her men; no secondary character remarks on how Joiry is unnatural for being commanded by a woman, and none of the foes Jirel faces (who run the gamut from relatively mortal wizards to unearthly sorceresses to vague, abstract supernatural forces) underestimate or undervalue her because of her gender at all. Nor is Jirel simply a palette swap of Conan the Barbarian. Several of the conflicts in the stories are driven by romantically or at least sexually charged encounters rather than overt violence; Black God’s Kiss is maybe my favorite in the collection because despite being a swords-and-sorcery revenge story, the story also captures the erotic tension of competition and rivalry well.

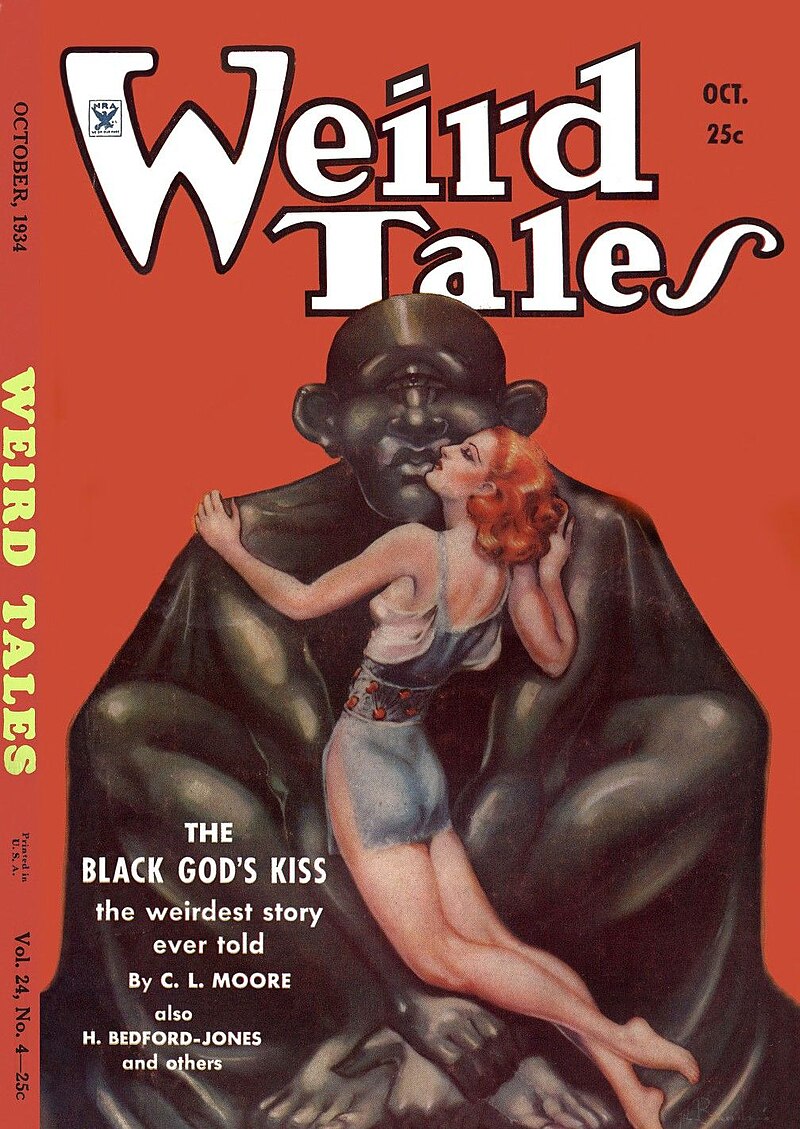

With that all said, I’m not entirely thrilled with the cheesecake cover art of this edition of the collection. I guess boob armor and tactically inadvisable exposed skin is now a fantasy art trope, but it clashes with Jirel’s actual character. Her dress is invariably actual armor, a doeskin tunic, or some kind of fancy gown. It seems to miss the point to take a pioneering woman fantasy protagonist and give her the Heavy Metal treatment. Of course, the original cover art for “Black God’s Kiss” isn’t really a proper representation either:

Overall the stories were fun and compelling, and I really wish that Moore had used them to launch into a full-length novel so we could spend more than an hour or two at a time with Jirel and her world. Or, barring that, more than just six stories would have been nice. By contrast, Conan the Barbarian appeared in 18 stories published before Robert E. Howard’s death—not counting Conan-adjacent pieces and posthumously published works. Perhaps if there had been an equal volume of Jirel of Joiry stories, she’d have her own beefcake cinematic avatar to cement her place in pop culture history.

It’s not too late for that, I suppose! I nominate Ronda Rousey for the role.