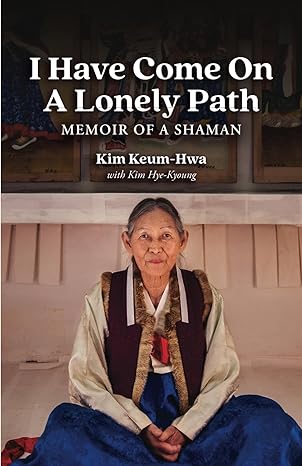

Seo Choi has put out multiple successful Kickstarter projects, including several books, that highlight various aspects of traditional Korean spiritual practices. The latest one that just went to print was Keum-Hwa Kim’s I Have Come on a Lonely Path: Memoir of a Shaman. (Original Korean: 비단꽃 넘세)

According to Choi’s initial Kickstarter description, the original edition of I Have Come on a Lonely Path published in 2007 was popular enough to be made into a movie, but fell into obscurity (or maybe just “hard to obtain” territory) when the publisher went out of business in 2011. An American friend of Choi’s happened to have a copy and gave it to Choi, who has made it available for the first time in English through her micropublishing company Alpha Sisters. I supported the Kickstarter at the ebook tier and received my copy back in April.

The book isn’t especially long; I read the entire thing on commutes, lunch breaks, and waiting for friends at bars. The chapters are relatively short so you can dip in and out as you have time. Peace Pyunghwa Lee’s translation is excellent, with plenty of explanatory footnotes for historical context and specific cultural or technical terminology—the names of items of clothing, food, or particular rituals and so on.

Through Lee’s translation, Kim presents her story directly, without needless digressions or flowery ornamentation. The introduction to I Have Come on a Lonely Path includes a content warning for “domestic abuse, physical violence, war, mental illness, suicide, poverty, police brutality, and discrimination” but the depictions thereof were rather plain and brief. I’ve read much more unsettling accounts, in fiction as well as non-fiction. Through it all, Kim remains humble, compassionate and empathetic. We follow her from her birth in 1931 in what later became North Korea, through early poverty and her shamanic initiation as a teenager, to her middle years living on the fringes of society in South Korea, until the latter stage of her life as a recognized carrier of intangible cultural property (the Seohaean baeyeonsingut) with performances in the US and on live South Korean television, a feature-length biopic, and the founding of her shrine on Ganghwa-do. She speaks frankly of these accomplishments without any sense of self-aggrandizement, maybe because the struggles of her early years kept her humble. First and foremost for Kim is the preservation of a tradition and living a life of service; those honors seem to be more about that preservation and service than about herself. She also lived through interesting times, as the expression goes. We don’t get any commentary on the titans of twentieth century Korean history here, however. Kim only mentions events directly impacting her or her clients. This is mostly in the form of ill-tempered Japanese officials or South Korean discrimination against North Koreans, but to my embarrassment her story was also the first I’d heard of the New Village Movement.

In light of the New Village Movement, particularly the less savory aspects that bring to mind Mao’s Cultural Revolution, translation projects like I Have Come on a Lonely Path are important for maintaining the traditions and integrity of a culture. The thought struck me sometime afterwards that in some ways it’s comparable to the translation movement in Arabic that preserved so many manuscripts in Greek and Latin for scholars in Medieval Europe to rediscover and to include in the early years of the European academic tradition. Sometimes knowledge, ideas, and stories need to drift from one language or culture to another to ensure their own longevity. Power consolidation, especially within the structure of colonialism, is often based on rendering these ideas forgotten.

Overall this was a quick and fascinating read, at least for any Koreaboo (such as myself) curious about Korean folklore and traditions. The English edition includes an afterword from Kim’s niece, who continues in the same shamanic tradition (she is Kim’s “spirit daughter”—mentee—in addition to being her brother’s daughter) and currently maintains the shrine Kim established on Ganghwa-do. If it’s not your bag, it’s not your bag, but in the informal itinerary I’m building for my next trip to Korea I just added Incheon and Ganghwa-do.