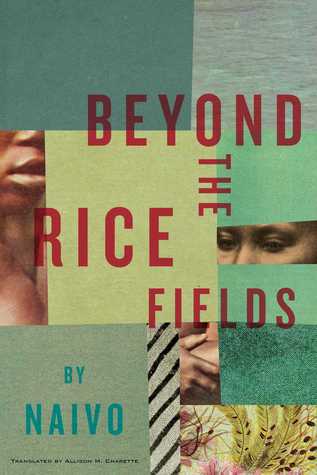

Beyond the Rice Fields was a Facebook book club selection for September; I finished it in the middle of October. Sometimes it takes me a while, but I get there!

Author: Naivo

Translator: Allison M. Charrette (French)

My GoodReads rating: 3 stars

Average GoodReads rating: 3.76 stars

Language scaling: C1

Content warning: A fair amount of off- and on-screen violence and gore

Summary: The clash between Christian missionaries and the ruling elite of Madagascar as it plays out in the lives and loves of Fara and Tsito.

Recommended audience: Anyone curious about the pre-colonial history of Madagascar; anyone looking to read more African literature

In-depth thoughts: This is a completely petty point, but once I realized that Beyond the Rice Fields had been translated from French instead of Malagasy, I lost a lot of steam. Not because of anything wrong with the book, but rather because I always feel a little guilty and uninspired when I read an English translation of a work originally written in a language I can more or less read (Swedish, French). But I didn’t realize that when the book turned up for book club, and so I didn’t even think to see if I could find the French edition anywhere.

My pettiness aside, the book is beautifully written. I savored the prose even when I knew tragedy was just around the corner. Naivo’s writing has a lyricism and a rhythm that’s utterly captivating, though that doesn’t stop the plot from feeling like it’s dragging at certain points. And it’s not even a dragging plot that I mind; it’s that it moves so relentlessly and so slowly towards tragedy. (Spoiler alert, I guess: the ending is a downer.) I’m willing to slog through hell and high water if I think the protagonists will get their reward in the end, but when things become a slow motion trainwreck it’s a little harder to bear. Especially when it feels like a deus ex machina trainwreck.

The most satisfying endings and character arcs are when someone gets what they deserve, for better or for worse. When bad luck and misfortune constantly befall a character, and when they’re undone by chance and circumstances rather than their own poor decisions or character flaws, their tragic end is so much less satisfying. That’s my one-sentence critique of Beyond the Rice Fields: the tragedy feels senseless and unearned. It’s just plain bad luck. Of course, tragedy in real life is often senseless and unearned. I just want something else from fiction, especially right now.

For EFL readers, Beyond the Rice Fields might be hard work in places; among other things, Naivo has a tendency to stack lengthy modifiers on top of each other:

A scarlet curtain was visible in the back, concealing a secret door, behind which I heard voices.

But this complex construction also gives the prose its lullaby-like quality. If you can’t read the French original, Charrette’s English translation is beautiful and rewarding.