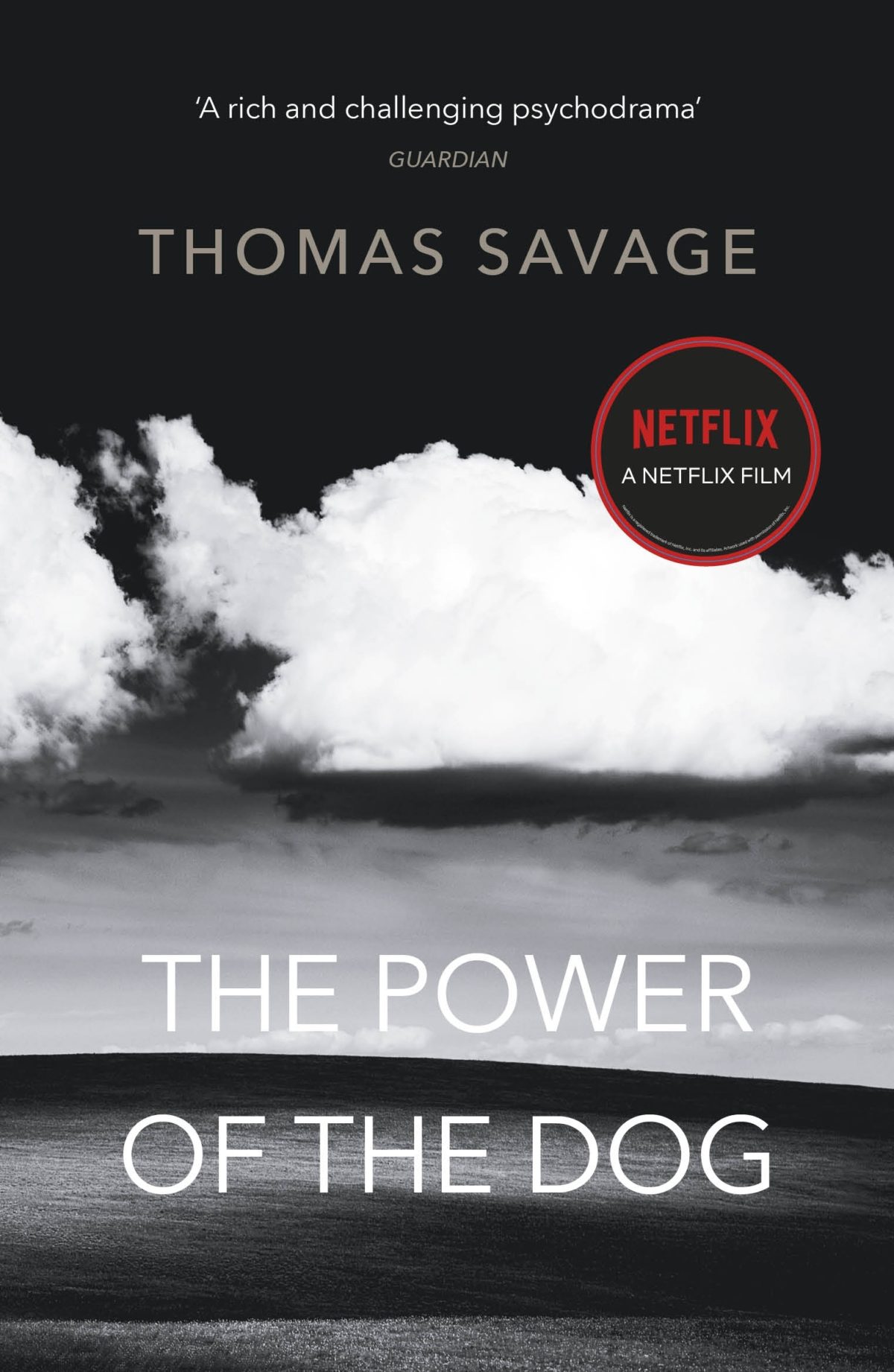

Back in January I was having a few beers with the same friend who recommended The Power of the Dog and we got on to the topic of Elmore Leonard.

“Stick! There’s one for you. Classic Leonard.”

Elmore Leonard is a legend and there’s nothing interesting I can add to the conversation about him. What’s noteworthy is that I read Stick in English (available from the good people at archive.org) and then, immediately thereafter, the Swedish translation by Einar Heckscher. Unlike the last time I became fixated on a translation (Gösta Berlings saga), there’s only one translation (so far as I’m aware?) and thus no comparisons are possible.

My drinking companion was adamant that no Swedish translation of Elmore Leonard could possibly work. I didn’t really have an opinion one way or another, maintaining neutrality as a professional courtesy to a fellow translator. Nonetheless, I’m a hyperactive golden retriever when it comes to talking about books, and once I cracked open the Swedish version he was subject to a slew of random WhatsApp messages, complete with screenshots and photos, whenever I thought a particular translation choice was interesting. Which, despite heroic efforts on my end to practice at least a modicum of restraint, was still pretty often. Sorry, Richie!

This translation of Stick came out in 1987, essentially contemporaneously with the 1985 original, as I guess is usually the case with popular commercial fiction. My biggest takeaway from the book, just viz a viz translation, was, “The internet is a life-saver.” How many times a day do I dump a term into Ecosia, Linguee, Folkets, Google ngrams, whatever else, just to wrap my head around it? How do you handle running up against the brick wall of foreign slang when you don’t have instant answers at your fingertips? If you can knock that one down, how do you dig through the slang of your own language beyond the scope of your personal usage? This is how I ended up asking my sambo and coworkers and bilingual friends how they would translate the recreational drug term “mainline” into Swedish.

My second thought was to wonder what a new translation would look like if it came out today. I think a lot more of the English would remain as calques, or be only moderately “Swedefied,” and I think there’d be a fair amount of förortssvenska. (Förortssvenska was already a thing when the book came out, but I don’t think the nearly-50-year-old Heckscher was spending a lot of time with teenagers in Rinkeby.)

My third thought was to go down a rabbit hole on the topic of Einar Heckscher himself, just because there’s actually information about him online. There’s a whole back catalogue of Swedish culture that I can’t ever hope to catch up with, and Heckscher is one of many, many items in there. I only learned about him, and by association the rest of his highly accomplished family, because I was curious about who translated this Elmore Leonard novel—judging by at least a couple Flashback posts,* though, I should have already been acquainted with Heckscher as a 70s prog rock figure from bands like Sogmusobil and Levande livet. A couple of interviews in Svenska Dagbladet and Socialpolitik got me up to speed, as did a couple of obituaries. Son Björn is hard to track down anywhere online, but his daughter at least followed in her father’s footsteps and translated? contributed to? a Swedish collection of Bukowski. Hard to say, since her father was also celebrated for his Swedish translations of Bukowski and that appears to be her only published work to date.

Incidentally, the Swedes on Flashback seem largely to share my drinking companion’s spitting rage at Heckscher’s translations, which can roughly be summed up as:

Han förvandlar allt till buskis och pilsnerfilm och förvränger allt han kommer över.

*Apologies for linking to The Bad Place, but as Flashback threads go it’s pretty innocuous.

Another point in favor for those left-field, organic and algorithm-free random book recommendations. Without the prompting and social context, would I have bothered to dip back into Elmore Leonard after a twenty years’ absence? Would I have gone down this weird little rabbit hole of Swedish prog rockers, politicians, and pundits? Absolutely not. But now I have, and so have you, and knowing is half the battle. G. I. Joe!