Balsam Karam is my most recent Baader-Meinhof phenomenon: I first heard of her when an Internet associate announced that he had been invited to host a panel discussion called “Read the World,” with Karam as one of the guests, at the Fold literary festival. Not long after that, a précis by Karam about Brazilian author Jeferson Tonorio was featured in the issue of Karavan I was reading at the time. Then when skimming the events for Litteraturmässan I saw that she would holding a talk with Peter Englund about the role and potential of libraries. Three points make a line and all of that.

I looked up Karam as soon as I learned she wrote in Swedish, always trying to fight the inertia to read books in English by default. If the timestamps in Discord conversations are anything to go by, then, I’ve been working on Singulariteten since February 20. I have Händelsehorisonten on deck, too, but Singulariteten was just so much that I might admit defeat with Händelsehorisonten for the moment and save it for later.

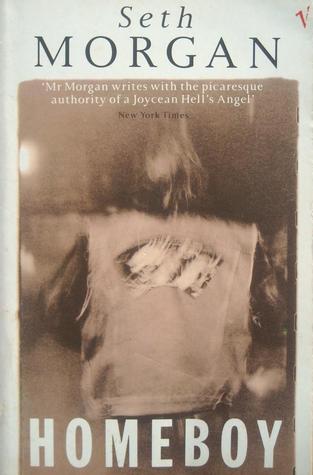

Singulariteten is a tale told backwards, starting at the end of two stories, two lives. The paths of two nameless women cross, briefly, along a trendy corniche in the tourist district of an unnamed country recently emerged from (or perhaps still intermittently engaged in) sectarian violence. One of the women is a mother in search of her missing daughter; the other is a pregnant tourist who witnesses the first woman’s suicide. Later, back home, she has a miscarriage. Out of this intersection unfolds lifetimes of loss and trauma, as the rest of the book looks back to tell each story in its entirety. The whole thing is so grim and heavy that I was surprised when the living, breathing Karam in the discussion on stage was light, breezy, quick to laugh and quick to make jokes. Serious emotional whiplash.

Which is not to say that Singulariteten was so dour and joyless that I didn’t enjoy it; I came out the other end with a sense of satisfaction and catharsis (Aristotle would be pleased). This was due in part to the dense, complex language that forced me to read passages multiple times and to construct little sentence diagrams in my head, so all credit to English translator Saskia Vogel for excellent work. This isn’t Karam’s first novel, but thanks to Vogel it’s the first available in English.

The topic matter does prompt reflection over the kinds of novels we expect from certain kinds of authors. I want to say that there’s a James Baldwin essay, perhaps his own commentary on Giovanni’s Room, on the limitations of being expected on certain topics (in Baldwin’s case, racial discourse) simply by virtue of a facet of one’s identity (race), but maybe that essay doesn’t exist. Maybe I’m thinking of (and misremembering) “Everybody’s Protest Novel.” Unsure. But there is a tension for me because I can’t help wondering: for a Kurdish author like Karam, do publishers, reviewers, readers expect a certain kind of book? If Karam had instead written an easy read feel-good romance, would it still have been published? (I have every confidence that it still would have been good.) Or do themes of being marginalized, racialized, and elsewise Othered have a demonstrably limited appeal to a mainstream audience that mean they get scrubbed down and sanitized? (Thinking again of Giovanni’s Room, which Baldwin was advised to burn lest it alienate his audience.)

Nell Irvin Painter to the rescue, with this essay for LitHub that I got in my inbox this morning but that is not yet available on their website.

I asked: who can I and we write about when I and we are Black authors? Those accomplished authors I mentioned [Imani Perry, Honorée Fanon Jeffers, and Zora Neale Hurston] wrote about Black people, and Black people and race in America are the subjects of virtually every book by a Black author of fiction, of nonfiction, and of journalism. I’m tempted to conclude that literary convention limits Black authors to a limited range of subject matter. Yes, there’s infinite variety within the realm of Blackness. Yet still, Black people only.

Painter is describing an English-language publishing industry with an American audience, but I think there are parallels to be made with Sweden. In the end I suppose I just have to trust in the fact that Singulariteten demonstrably exists, and take the book as proof of the fact that Karam wanted to write a story, any story at all, and accept that speculation about how that story may or may not have been crafted according to particular expectations from her publishers as unknowable and therefore irrelevant.