I normally don’t pay attention to awards in real time. If I’m browsing a bookstore and I see that a particular book has won this or that prize, it might push me towards buying it rather than putting it back. But nominees? Voting? Nah. I’m still prioritizing my Classics Club journey through the TIME Top 100 Novels list, so I’m not really up to date on new releases (except the ones I get from NetGalley and Blogging for Books).

But sometimes I catch wind of things and my interest gets piqued. That was the case with The Three-Body Problem—and that was mostly because of the Puppies Hugo debacle. Chinese science fiction? Sign me up!

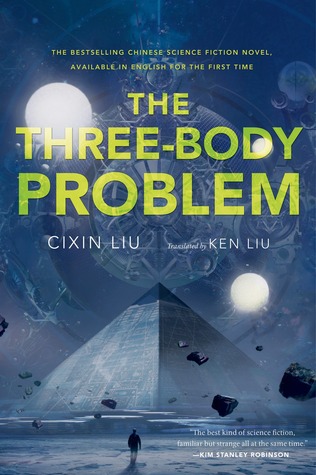

Author: Cixin Liu

Translator: Ken Liu

My GoodReads rating: 4 stars

Average GoodReads rating: 3.98 stars

Language scaling: B1/B2+

Plot summary: Nanotechnology expert Wang Miao becomes sucked up in a covert government plot, dating back to the Cultural Revolution, to manage humanity’s first contact with an alien race.

Recommended audience: Fans of hard science fiction; people interested in quantum physics.

In-depth thoughts: The Three-Body Problem is a first contact novel that is very much informed by contemporary breakthroughs (the Large Hadron Collider) and theories (quantum entanglement). It’s an interesting companion piece to The Sparrow, where the scientific expertise isn’t in the tech or the theory but in the culture- and race-building.

A comparison between The Three-Body Problem and The Vegetarian is also warranted. Technically, Chinese and Korean are members of different language families (Sino-Tibetan and Koreanic*), but it’s safe to say they are both equally alien to English. Smith and Liu probably faced similar problems regarding not only language but also culture. The Three-Body Problem is steeped in China’s modern history; The Vegetarian in Korean cuisine. Among many other small things, both languages have particular forms of address (especially within families) we don’t use in English.

But there are more subtle issues involving literary devices and narrative technique. The Chinese literary tradition shaped and was shaped by its readers, giving rise to different emphases and preferences in fiction compared to what American readers expect. In some cases, I tried to adjust the narrative techniques to ones that American readers are more familiar with. In other cases, I’ve left them alone, believing that it’s better to retain the flavor of the original.. . .The best translations into English do not, in fact, read as if they were originally written in English. The English words are arranged in such a way that the reader sees a glimpse of another culture’s patterns of thinking, hears an echo of another language’s rhythms and cadences, and feels a tremor of another people’s gestures and movements.. . .In moving from one language, culture, and reading community to another language, culture, and reading community, some aspects of the original are inevitably lost. But if the translation is done well, some things are also gained — not least of which is a bridge between the two readerships.

Translation notes aside, I only had a small problem with the book. Science fiction has not always been a genre that lends itself to nuanced, mutli-layered characters—often we have a few given archetypes that are faced with a predicament, and the narrative thrust isn’t about their journey as characters but about how the problem is solved. The same tradition seems to have informed The Three-Body Problem as well, though Liu Cixin doesn’t mention any of his science fiction influences or heroes in his afterword. The characters in the story are largely archetypes or just stand-ins; plot points for a story rather than flesh-and-blood people. The exception is Ye Wenjie, who I thought was interesting and compelling. I wish she was in the story more.

Overall it was a great hook for a trilogy. Once I finish Swedish class, I’ll definitely be picking up the sequels as a treat for myself.

*Korean is sometimes grouped in with Altaic languages and sometimes considered its own isolated family. Either way, it’s not linguistically connected to Chinese the same way that English is connected to, say, German.