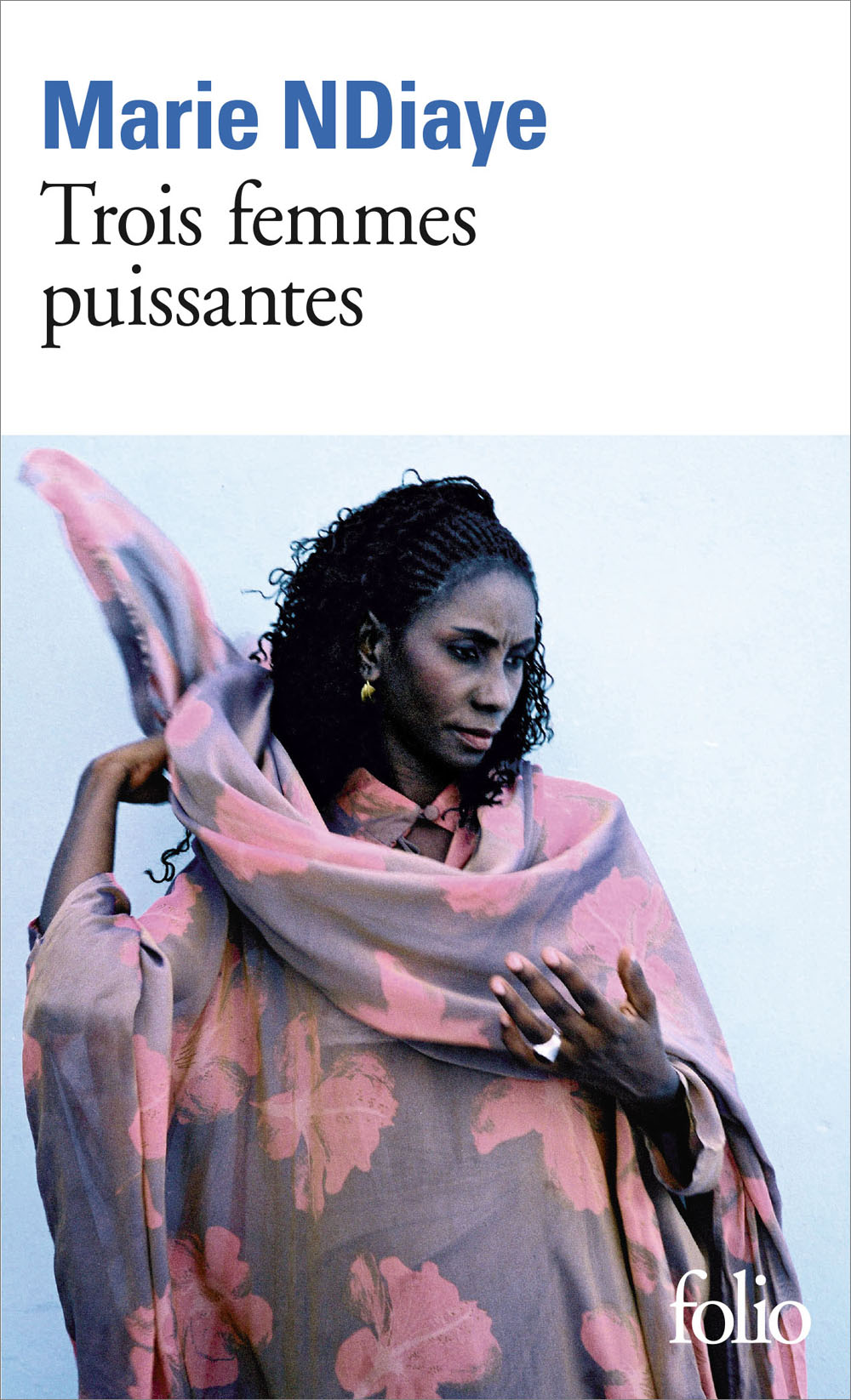

After I fell in love with Marie NDiaye through La Vengeance m’appartient, I was thrilled to find out that the Stockholm library also had Trois femmes puissantes. In French, Swedish, and English to boot!

I racked up a late fee in excess of SEK 200 in order to really suck the marrow out of this one, though there were long periods where I just didn’t have the time or the mental capacity to engage with French. My insistence on reading sections in French, then Swedish (Ragna Essén, translator), then English (John Fletcher, translator), then French again means that the 230-odd pages ballooned into nearly 1,000 pages. I forgive myself! Even if this very nearly tanked my French reading goals for 2024!

Trois femmes puissantes is a collection of character sketches of three women whose lives are (possibly?) loosely intertwined. First we have Norah, a successful lawyer who has returned to her father in Senegal on an urgent matter—mounting the legal defense of her beloved brother, who stands accused of killing his stepmother with whom he’d been having an affair. Then we have Fanta, though her story is told through the perspective of Rudi, her French husband. We meet the couple destitute in France, several years after being forced to leave Senegal. Finally we have Khady Demba, a young Senegalese widow who finds herself forced to emigrate to Europe.

The thematic elements of parent-child relationships and the ripple effects of toxic masculinity connect all three stories, though there are hints or more explicit material links as well. We actually first meet Khady in Norah’s story, as a domestic worker in her father’s house. Norah’s father acquired and then lost a substantial amount of wealth through the ownership of a tourist village in Dakar—one that Rudi’s father may or may not have been engaged in constructing. (NDiaye doesn’t make it clear either way; I decided to read it that way because it gives a nice symmetry and mutuality to all the relationships among the women.) And finally, we learn that Fanta is a distant relation of Khady, and it’s the prospect of Fanta’s imagined wealth in France that sets Khady on the road to Europe.

Like in La Vengeance m’appartient, NDiaye leaves a lot of questions unanswered. Norah’s and Fanta’s stories end fairly inconclusively: we don’t know the outcome of Norah’s trial, we don’t know whether Rudi’s epiphany will materially change the quality of Fanta’s life. Only Khady’s story ends with a clear, decisive outcome. All three stories were fantastic; Norah’s was my favorite, because I found Norah’s ambiguous relationship with her father so compelling, but the way NDiaye builds tension and suspense in the other two is just superb.

However, once again I have to note that I was annoyed by the English translation. At this point, maybe I just have to admit defeat when it comes to French. I didn’t like the English translation of La Vengeance m’appartient, either, but that was a different translator (Jordan Stump). If two different translators both produce fairly similar translations of the same author, then I’m willing to admit that the problem is me. I’m by no means fluent in French; I don’t have an inner ear attuned enough to judge French prose for being clunky, or old-fashioned, or exceptionally beautiful. It’s back to the Pevear and Volokhonsky debate all over again: sometimes the original is just plain awkward.

That said, while Fletcher doesn’t seem to have much of his own commentary out in the world, the little I read in this article by Lily Meyer over on Public Books didn’t necessarily endear him to me. I didn’t care for Stump’s writing style in interviews, either, but he at least didn’t come across as ambiguous or even hostile to NDiaye’s writing as Fletcher does here. And I’ll keep throwing myself at the brick walls of NDiaye’s writing because whatever my level of competence in French may be, there is something in her writing that I find magnetic and spooky.

2 thoughts on “Trois femmes puissantes”