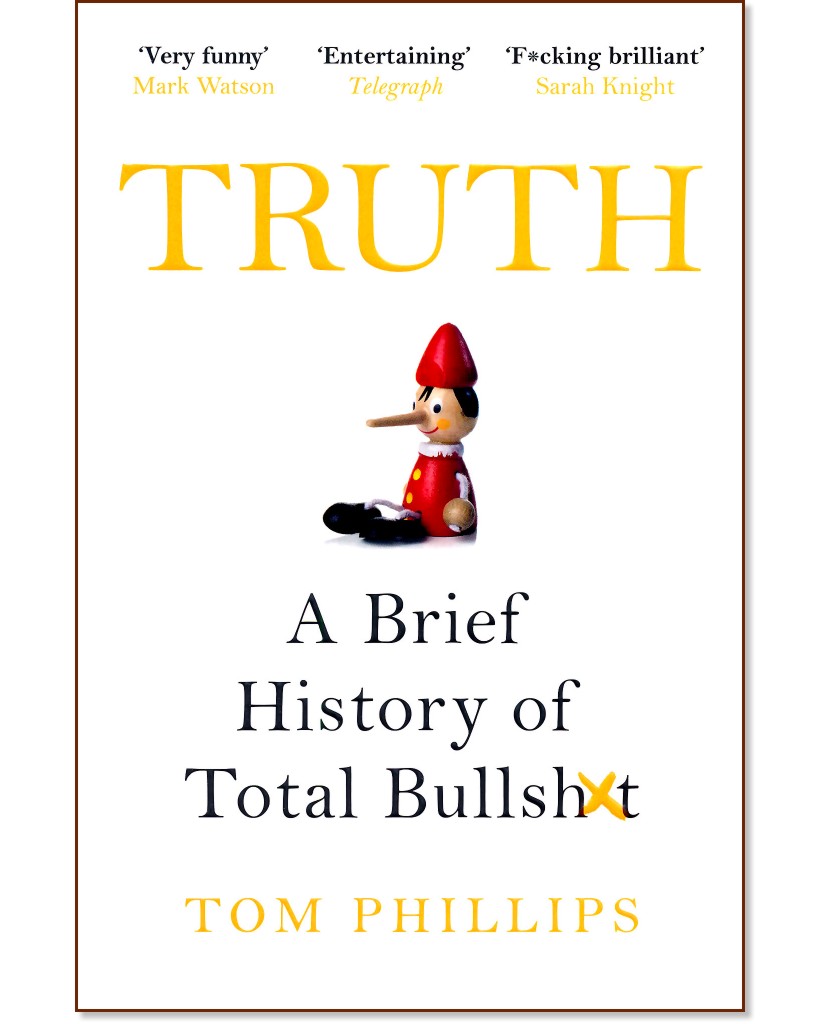

My frazzled brain has recently been unable to focus on the kinds of things I usually enjoy, so I took the opportunity to finally read a birthday gift I received earlier in the year: Truth: A Brief History of Total Bullshit. I like it and breezed through it in a couple of days, but my brain is perhaps still too frazzled to have a coherent thought about it. Let’s give it the old college try.

Author Tom Phillips (formerly of Buzzfeed UK) lays out a tasty little buffet of, well, “total bullshit.” Published in 2019, it’s very much a response to the burgeoning concern with fake news; to the extent any pop history book has a more serious agenda beyond mere entertainment, Truth serves as a reminder that people have been creating and spreading fake news forever, so let’s all take a deep breath and not panic over it.

First Phillips establishes the difference between bullshit and lies, as well as the myriad ways in which we can get things wrong or perpetuate untruths. A bit of theory, if you will. Then the rest of the book covers a wide variety of lies, grouped by topic: news and journalism, hoaxes, specious geography, con artists, politics, business, and finally mass delusions before rounding off with a conclusion about how we can get better at spotting all this.

I mentioned that Phillips was formerly of Buzzfeed UK because the kind of brisk, ironic writing (and occasional profanity) that characterizes popular Internet journalism permeates Truth from beginning to end. It had the nostalgic flavor of Cracked.com circa 2010 or so. Which is not necessarily a criticism! That was exactly the challenge level my brain was capable of at the time and I had a lovely time reading it.

Not that I would have pooh-poohed Phillips’ approach if I felt like my faculties were firing on all cylinders, either. There comes a point with non-fiction where an author has to decide what kind of book they’re going to write and why they’re interested in writing it. Who’s the target audience? What do they hope people will take from it? What’s the best way to potentially change people’s minds, or inspire them to action, or just help them learn something? My own inference is that the dizzying number of anecdotes Phillips presents is not out of a desire to trace the evolution of lying or to make a strong philosophical claim about the nature of bullshit (Harry G. Frankfurt has that covered). I think his motivation for the entire book comes through in the last chapter, with suggestions for how to become more discerning about truth and untruth.

In other words, couched though it may be in jokes and amusing anecdotes, Truth is a book-length appeal to the reader to stop and think for a minute before you share that inflammatory news story you just saw in your feed.