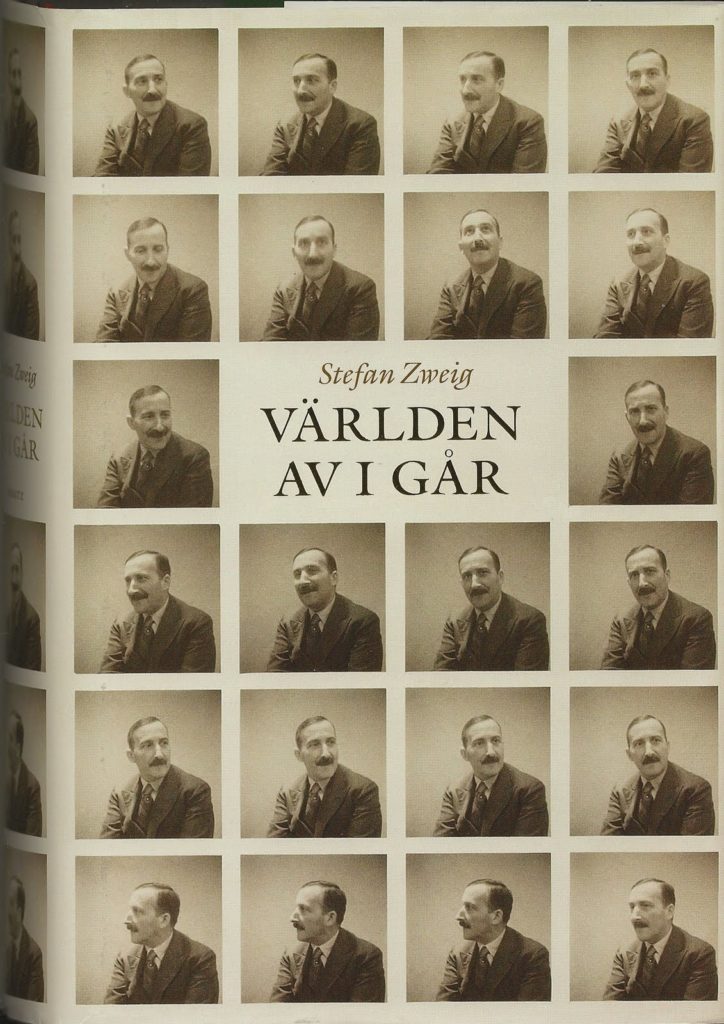

It seems I followed much of the rest of the world, or if not the world then just one friend of mine in particular, in reaching for Die Welt von Gestern in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election. But since my arbitrary rule of translations is to read German originals in Swedish rather than in English, I had to wait until I came across a Swedish translation (and it never seemed to be available at the library when I remembered to check). Six years later, it appeared in front of me at Söderbokhandeln Hansson & Bruce. I took it with me for vacation reading, and while I was browsing Hubenettes in Östersund I happened to notice Zweig’s novella collection Amok on the shelves. Since they’re the same author and I read them in such close succession, collapsing them into a single blog-thought makes sense.

Amok is not any deliberate assemblage of Zweig’s or time-honored collection that’s seen international release in several languages. Instead, it’s a collection from Ersatz Förlag, only available in Swedish, featuring “The Royal Game,” “Twenty-Four Hours in the Life of a Woman,” “Confusion,” “A Girl and the Weather,” and “Amok.”

The World of Yesterday, on the other hand, is available in several English translations: one from titan among translators Anthea Bell, which seems to be the translation put out by Pushkin Press; one from Plunkett Lake Press attributed to B. W. Huebsch and Helmut Ripperger; and finally a translation from Robert Boettcher independently published through Amazon.

Let’s get the obvious out of the way: Zweig doesn’t really discuss his own writing much in Världen av i går, at least from a personal perspective on the process. The only time he addresses the craft of writing more or less head on, he toots his own horn and talks up how one of his strengths as a writer is his ability to murder his darlings and stick to only the most essential elements of a story. After the five stories included in Amok, I have to disagree, but maybe that’s a factor of changing times and literary conventions.

Women are essentially invisible in Zweig’s depiction of Europe in general and of his life in particular. Not surprising for the content or the times, so I’m not exactly mad about it. Nonetheless, it’s worth pointing out that Zweig’s first wife (who only gets two incidental mentions in Världen av i går, one of which is when Zweig is trying to divorce her) undertook a significant chunk of research and administration for him; his second wife (whose only mention is in the same breath as the aforementioned divorce) had originally been his secretary. Amazing how being able to outsource drudgery and life maintenance frees you up to be a highly productive writer!

The same lack of women more or less applies to the stories in Amok, which are all deeply anchored in a first-person perspective from a male narrator. Even “Twenty-Four Hours in the Life of a Woman” uses a male narrator to frame the story of the woman in question—a frame that I don’t see much narrative use for. Of course, Amok only contains five novellas out of a substantial body of work; such a limited selection is hardly indicative of an entire body of writing. I just wish there had been more thought on the publisher’s part about which stories to select.

Overall, I was touched by Zweig’s humanity and empathy, which was just as much on show in the above stories as it was in his memoirs. They are all deeply psychological, character-driven narratives rooted in human struggles, suffering, and resilience. But in all honesty, his knack for characterization is actually on better display in Världen av i går than in most of the stories in Amok. Zweig’s sketches of his contemporaries are precise and cutting, unambiguously sympathetic to the person involved but clear-eyed about their flaws or failures. The characters in the stories collected in Amok, on the other hand, are muddier and harder to pin down. I cried at some point in every chapter of Världen av i går, but I shed no tears over any story in Amok.

The reason I was so unmoved by, and ultimately a bit disappointed in, Zweig’s fiction might be the same reason I could lose myself so easily in his memoirs: they are a product of a specific time. Sympathy for an amorous widow scorned by a younger lover, or for a closeted gay English literature professor, might well have been scandalous or at least unusual upon publication in the 1920s, but close to a century later those stories are fairly tame and predictable. So the wheel turns; with any luck, in another hundred years, stories like “I Sexually Identify As an Attack Helicopter” will seem confusing or just banal because we’ll live in a better world where fluid gender identities are a matter of course. While Världen av i går might as well be subtitled “Plus ça change,” stories like “Confusion” with their now-dated and unremarkable plot twists make you realize that things can get better.